The Weight of Memory

Eunice Sanchez on her photographic practice.

Words Marz Aglipay

Photos courtesy of Eunice Sanchez, Earvin Perias, Carlo Gabuco, and West Gallery

December 06, 2025

Photo courtesy of Earvin Perias

Eunice Sanchez, a Manila-based cultural worker and artist, has been steadily gaining recognition for her image-based practice that questions perception and memory. She recently concluded Sa Lukong Ng Mga Palad (In the Hollow of Palms), a two-person exhibition with Carlo Gabuco at Finale Art File, and was shortlisted for the 2025 Fernando Zóbel Prizes for Visual Art for her solo exhibition Sa Ilog Nagtatagpo (2023). These milestones highlight the trajectory of a practice that bridges photography, alternative processes, and cultural work.

Her work feels less like a record of reality and more like an echo of memory, unfolding through cyanotypes and photographs. She isn’t interested in simply capturing a moment, but in testing how perception itself holds onto it.

Photo courtesy of Earvin Perias

Sanchez, born in La Union in 1993, comes to art through multiple doorways: psychology, photography, and cultural work. “Both fields share a concern with perception, memory, and human experience,” she told me. “But for me it goes beyond psychology. The foundation I gained from the humanities continues to inform the way I approach projects, particularly those centered on research and human engagement.” Her entry into cultural work, where she has found mentors and colleagues, keeps her grounded. “As a colleague once said, ‘You do not open wounds and close them up in three days.’ This keeps me mindful of the responsibility such work requires.”

Photography first came to her through a family album. “Have you ever carried a hazy fragment in your mind only to realize it’s real when you came across it in a photo?” she asked. For her, it was a small Christmas tree she thought she had imagined—until she saw it in an old photograph taken by her mother. “Finding that photo was validating. It felt good to know I hadn’t just imagined it. That moment became my earliest awe of what photographs can do.”

Sanchez, Eunice, Pagsibol,Cyanotype print on paper , 10 x 8 inches, 2023, Photo courtesy of West Gallery

She carried that awe into adolescence, taking pictures with her Sony Ericsson Walkman phone, filling it with images as eagerly as she filled it with music downloaded from Limewire. “I always wanted a record, some kind of proof. I wanted so many things to last.”

In her schooling—first at De La Salle University, then at the College of Saint Benilde— was where she began to find her people. At the student publication, Malate Literary Folio, she fell in with a circle of writers and artists who were, like her, trying to make sense of art-making beyond the strictures of a fine arts degree. The group became her ballast during those disorienting first years in the city. “It softened the complexities of adjusting,” she recalled. “All of these amounted to what I do and what I am now.”

Eunice Sanchez, tides hold names IV, Photo courtesy of Carlo Gabuco

Sanchez’s art doesn’t cling to permanence; Instead, it lingers in the fragile spaces where memory reforms. In Sa Ilog Nagtatagpo (2023), shortlisted for the Fernando Zóbel Prizes for Visual Art, she traced the delicate rituals of loss. She asked herself a simple, unanswerable question: beyond religion and family tradition, how do we say goodbye to the dead? At first the exhibition felt private, almost indulgent, “a luxury to imagine what pain and yearning might look like,” as she put it. But viewers reached out. They told her the work echoed their own mourning, made them feel less alone. What she had forgotten, she realized, was that grief is the one universal.

That spirit of vulnerability carried seamlessly into Sa Lukong ng mga Palad (In the Hollow of Palms) (2025), Sanchez’s two-person exhibition with Carlo Gabuco. His canvases, charged with images of ruin and its aftermath, stood in counterpoint to her own meditations on water and memory—how the past, like a tide, returns to shape our sense of place and self. “Our practices met at the table—both literally and metaphorically—where unseen narratives and lived experiences intertwined,” she reflects. The show unfolded less as two artists presenting separate bodies of work, and more as a shared landscape: a space where relationships could coalesce and be reimagined.

Though Sanchez identifies foremost as an artist, she is just as devoted to her work as a cultural worker. The rigor she’s cultivated within institutions has sharpened her sense of discipline and accountability, while the studio remains her sanctuary for creative renewal. “The challenge has always been weighing what matters most in the present without compromising the future, while also maintaining consistency in both fields,” she reflects. Art, for her, is a privilege, but one that demands sacrifice—hours spent painting or printing often traded for lost sleep or moments away from family.

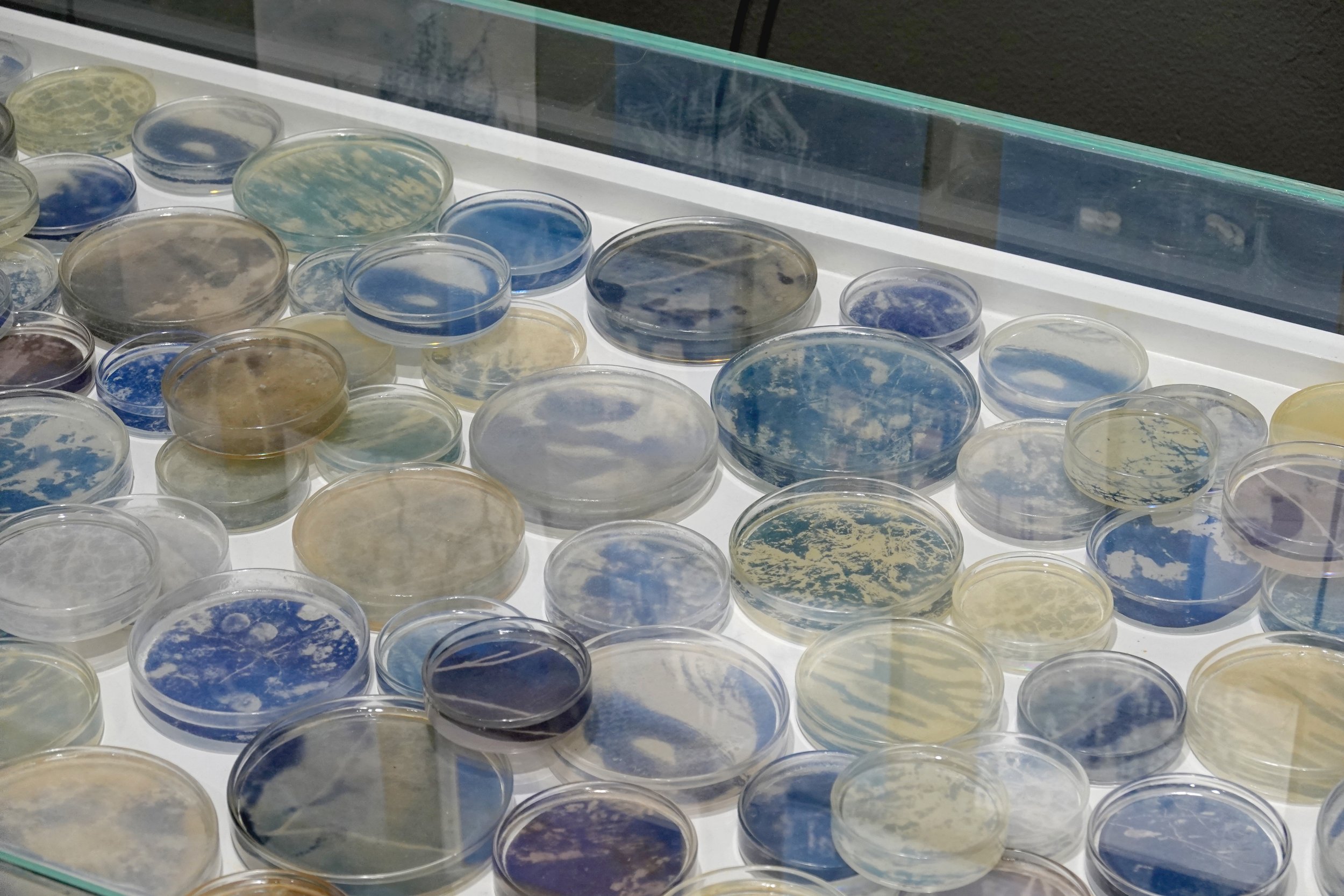

Her process begins not with materials but with an idea. “I re-evaluate constantly and ask myself what’s the best way to articulate,” she says. While her practice is anchored in photography, she lets it spill into other forms—cyanotypes, thread, fabric—materials that carry both intimacy and history. For Sanchez, tactility is inseparable from storytelling given the mediums she uses. “The material side really comes through once the image is printed. Prints can be touched, shared, passed around, or kept for sentimental reasons. They invite you to look again.”

Photo courtesy of Carlo Gabuco

That sense of wonder is something she witnesses firsthand in her workshops. “There’s always delight,” she says, recalling the moment when children realize they can create something beautiful with their own hands.

I wondered if her works are considered documents, interpretations, or something in between? “Perhaps something in between,” she answered. “Yes, they can be considered documents, but they’re not objective records. This is how I perceive and remember things. There’s nothing extraordinary in what I do, and I only hope to offer a way of looking.”

Eunice Sanchez, First Light,

These days, her inquiries into her practice feel less like answers waiting to be found but rather more like doors left open. “How far can my ideas really take me? What else can I do to keep my archive alive?” she wonders. Five years ago, she couldn’t have imagined taking residencies in Cambodia and the UAE, or the recognition that has followed at home. “But I also recognize that progress often comes from being part of circles where success is nurtured and empowered. There, you discover your own ways of giving back.”

Her work carries that spirit forward. Stitched with memory, history, and care, they resist disappearance. Each one a gesture of preservation, each one a quiet refusal to let what matters slip away.