Why Filipina Desire Always Under Suspicion?

Beyond gold-digger jokes and green-card assumptions, AFAM Wives Club reveals what cross-border love really looks like for Filipinas.

Words Gerie Marie Consolacion

Photos courtesy of iWant and ABS-CBN PR Facebook page

January 07, 2025

There’s something changing in the way stories are told. You feel it before you can name it. New film directors—especially student directors and young production teams—are no longer satisfied with safe plots and predictable endings. They want stories that linger. Stories that ask uncomfortable questions. Stories that reflect the world as it is, not as we wish it to be.

Film, at its best, does more than entertain. It listens. It speaks. It holds a mirror up to society and asks us to look longer.

That’s why voices once pushed to the margins are finally stepping into the frame. Queer people. Sex workers. Single parents. Women who refuse to apologize for their choices. These stories are no longer whispered. They’re being told out loud.

And AFAM Wives Club arrives right in the middle of this shift.

Welcome to the AFAM Wives Club

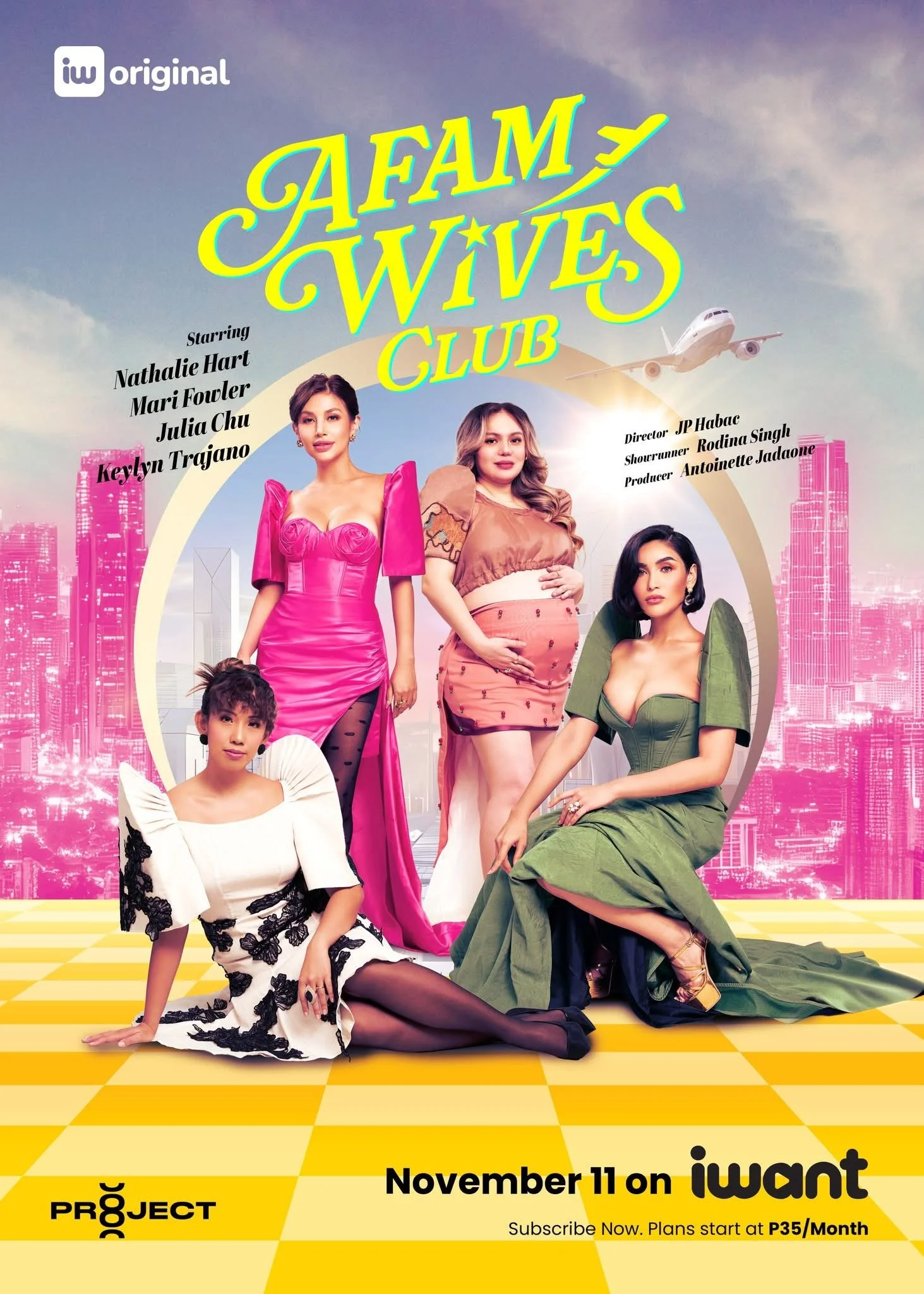

Directed by JP Habac, produced by Antoinette Jadaone, and guided by showrunner Rodina Singh, AFAM Wives Club follows three couples and a single mother as they navigate love across borders—love that is constantly judged, questioned, and reduced to stereotypes.

During the exclusive interview with the Art+ Magazine, Habac shares that he knew from the start that this wasn’t his story to control. “I started with curiosity and a lot of listening,” he says. “I didn’t want to tell stories about them—I wanted to understand what it feels like to walk in their shoes when it comes to love, culture, and societal expectations.”

That intention is felt in every episode. The camera doesn’t rush. It doesn’t interrupt. It stays long enough for silence to mean something. Habac describes his approach as raw but gentle, always grounded in care: “Laging may puso dapat.”

The series airs weekly, opening with a cocktail party where Filipina women and their foreign partners meet. It looks light at first, almost playful. But beneath the surface, something heavier waits.

Meet the women

Nathalie Hart walks into the show exactly as she is—an actress, a single mother, and someone who no longer feels the need to explain herself. She’s open to love, but she doesn’t chase it. If it comes, it comes.

She’s blunt. She’s bold. She’s not there to be liked.

She doesn’t flinch when people look at her a certain way. She lives by a simple rule: “Ayoko ng stress.” And somehow, that honesty becomes one of the most radical things on the show.

Alongside her are Keylyn Trajano and her Brazilian partner Luiz Catapam, Julia Chu and her Polish partner Michal Mazurkiewicz, and Mari Fowler with her American partner Landon Moore.

They don’t blur into one story. Each woman moves at her own pace. Habac explains it best: “Each had her own storytelling style, so we just followed their rhythm.”

Let the stereotypes burn

To love a foreigner as a Filipina is to inherit a set of assumptions you never asked for. Gold digger. Dependent. Opportunist.

Episode 1 doesn’t soften these labels. It puts them on the table and lets the women face them head-on. “The jokes and judgments are real,” Habac says, “but we reframed them—the camera listens and the women speak.”

What emerges is not a defense, but a truth. These women didn’t fall in love because of money. They fell in love because connections happened. And the show quietly dismantles another lie: that these women need saving.

Keylyn is financially secure. Nathalie moves freely because she can. Julia is a lawyer with her own firm. Mari owns the home she shares with her partner. Independence is not something they aspire to—it’s something they already have.

Then comes the ugliest stereotype of all: that foreigners choose Filipinas because they’re “less attractive.” Nathalie doesn’t just reject this idea. She exposes how cruel it is. Why do we degrade Filipinas so easily? Why do foreigners automatically seen as prizes?

Self-love is not a crime

By Episode 3, the show turns inward. Self-love becomes the focus, and with it, judgment follows. Plastic surgery. Dermatologists. Small choices that make women feel better about themselves somehow become public offenses.

Nathalie and Keylyn talk openly about doing these things not to please others, but to feel confident in their own skin. Why should that need justification? Why is a woman loving herself always seen as excess?

Habac knew these moments needed care. “Trust is everything,” he says. “We worked with a small, transparent crew—mostly women. It was important that the women always felt respected by the team, especially in moments of vulnerability.”

You feel that trust in the way the camera stays gentle, never invasive.

Love is imperfect

The same episode reminds us that love, no matter how real, is not simple.

Keylyn breaks down. She admits she’s happy with Luiz, that she feels supported—but happiness doesn’t erase fear. Money matters. Stability matters. Planning for the future matters.

Saying this out loud takes courage.

Love, the show seems to argue, is not just about choosing each other. It’s about choosing responsibility, again and again.

Episode 4 makes this even clearer when Luiz and Michal clash over something as small as basketball. Nathalie sums it up with a tired truth: “men and their egos.” What stings is how easily love turns into blame, how quickly a woman choosing herself becomes a problem.

An alien

Episode 5 softens the noise. Julia throws Michal a birthday party, beautiful and full of effort. Yet in the middle of it, he admits he feels lonely. Not ungrateful. Just lonely.

And Julia listens. This is where the show reveals something deeper. While these women are often accused of gaining more from these relationships, the truth is more complicated. Foreign partners leave behind families, friendships, and familiarity. They build lives in a place where they will always feel slightly out of place. They become aliens.

When Michal talks about wanting to return to Poland someday, Julia finally understands what he’s been carrying. Habac puts it plainly: “It shows the tension between how they’re perceived and who they really are. Strength, humor, and depth shine through, reclaiming their own narratives.”

So no, it’s not about a green card.

Afam Wives Club to friends

Beyond romance, the series also explores how hard it is to form friendships as adults. Walls are higher. Trust is fragile. Even shared experiences don’t guarantee connection.

Yet when it matters, these women show up for one another. They may not always agree. They may not always like each other. But when one is attacked or disrespected, the others step in.

There is power in that kind of solidarity.

For Habac, giving women the control over their stories was non-negotiable. “It’s very essential. This is their story, not mine. The camera witnesses, they decide what to reveal.”

And when the final episode ends, he hopes one feeling stays behind: “Empathy. Seeing these women as flawed, brave, funny, and whole. Questioning assumptions about love across borders.”

AFAM Wives Club doesn’t beg to be understood. It simply asks us to look again—and maybe, this time, look with care.

A new wave of storytelling

AFAM Wives Club doesn’t ask to be defended. It doesn’t polish its women to make them palatable. It lets them be messy, firm, soft, selfish, loving, and tired. And in doing so, it exposes the real issue: not who these women love, but how quickly we reduce them.

When the screen fades to black, the question isn’t whether love across borders works. The question is why Filipinas are still asked to explain themselves at all.