Stories of Araceli Dans

Araceli Limcaco-Dans raised ten children, at a time when homemakers did not have modern conveniences. Amid a bustling household, she created works of art that are testimonies to the fine balance she has achieved in a life fraught with trials, as well as comic moments.

Words Elizabeth Lolarga

May 22, 2024

Photo by Sandra Dans

FROM THE ARCHIVE

This cover story first appeared in Art+ Magazine Issue No. 16

She first entered my consciousness when, as a seventh grader at an all-girls' Catholic school, I saw her teaching art on television. Finally, we were no longer confined to lessons on sewing and embroidery that the nuns deemed appropriate skills for future homemakers.

It was a liberating time, that school year of 1968-69, when, for an hour each week, we watched the lectures of Mrs. Araceli “Cheloy” Limcaco-Dans on Educational TV (ETV), taped and broadcast from the Ateneo de Manila University. Then a week later, our art teacher, who trained with her, walked us through the application of the lecture. That first encounter with art was deeply embedded in my memory. There, before our eyes, Mrs. Dans held oil pastels and watercolors, brought colors to life on the blank sheets of a sketchpad.

I would be able to embark on my own journey to art making only much later when, at 49, with my two girls almost out of college, I found my way to Mrs. Dans' alma mater, the UP College of Fine Arts. Memories of those first art lessons with her on ETV came rushing back.

Mrs. Dans' own journey to where she is now, as a critically acclaimed painter whose works are much sought after by collectors, was fraught with trials, balanced by many comic moments. The early years of struggle are long over—she can now live comfortably for a year on the sale of one painting alone. As we sat with her that balmy afternoon in her studio overlooking a lush garden, she regaled us with a torrent of stories punctuated by a lot of laughter.

Her father, Eleuterio Limcaco of Navotas, Rizal, encouraged her inclination towards the arts. “Secretly, he enrolled me for art lessons at Santa Rosa College in Intramuros. I was a third grader in a class of adults who were taught to make scales and graphs to reproduce the exact replica of a photo. Looking back, it must seem like torture now, but I just obeyed. I wanted so much to learn how to draw. My mother, on the other hand, kept telling me, 'Stop drawing and drawing; you'll starve.’”

“By My Studio Window” (2006) Acrylic on Canvas

Artwork images from the artist’s collection, courtesy of Ayala Museum

She continued matter-of-factly, her father and mother, Regina Fernandez of Kalibo, Capiz, were, “always fighting because my Dad fooled around. He was good-looking; women chased after him and he yielded to temptation. Their fights were violent. Father would hold a gun; mother would wield a knife. My older sister Ofelia would referee.” Traumatized by this, Ofelia, a poet, became schizophrenic. Mrs. Dans and her husband, Jose “Totoy” P. Dans Jr., took care of her for 21 years.

Today, at 81, Mrs. Dans can speak of her parents dispassionately: “My father used to play polo. He was an insurance sales man who mingled with the rich and the famous. He became a member of The Manila Polo Club when it was still on Dewey, now Roxas Boulevard. We owned three or four Arabian horses in our three-hectare lot. There, he practiced polo and Ofelia rode with him. He lavished her with praise.” But Mrs. Dans didn't take to sports. “I just wasn't interested in them. I wanted to learn languages, ballet, take up voice lessons.”

Caregiving, however, is what comes naturally to her. Aside from Ofelia, Mrs. Dans also took under her wing her brother Ruben, better known as Fr. Fidelis Limcaco. When he fell ill with Parkinson's disease, she brought him home and installed him in her studio, which she equipped with everything necessary for his care. She hired therapists and male caretakers to see to his needs. Fr. Fidelis returned to the seminary only when he could wheel himself around and speak.

Somewhere in this family narrative is the love story of Cheloy and Totoy. She said, “I wasn't aware I was the campus belle at UP because I was too busy earning a living. After the war, our family property was mortgaged. To earn money, I painted portraits. Father then couldn't support us anymore because he had separated from my mother and was living with his mistress.” She continued,“Tia Monang Ramos (aunt of former President Fidel Ramos) put up a clubhouse for GIs. There, they met nice girls with whom they discussed books, played parlor games or sang songs. I drew pencil sketches of the soldiers, which I would finish in thirty minutes. I didn't charge a fee, instead I asked for art materials. When they returned to the U.S., several of their mothers, who were pleased with the portraits, wrote me and sent oil paints, brushes, drawing pencils, sketchpads, all of which I used in college.”

Those sketching sessions sharpened her skill in portraiture. At the UP College of Fine Arts, where she resumed her studies after the war, she sketched her classmates and did oil portraits, charging P20 each. Her mentors there included National Artists Fernando Amorsolo and Guillermo Tolentino.

At UP, she met engineering student Totoy Dans (a future minister of transportation and communications). She was attracted to him because he was “extremely bright, low-key, a gentleman who was also deeply spiritual. He was from the Ateneo, raised and mentored by Father John Delaney. Totoy was a valedictorian from kindergarten to high school, but he had no affectations. He had a strong sense of humor and an ability to make light of tragic matters.”

Totoy's parents (Jose Dans Sr. from Paete, Laguna, and Filomena Jalandoni Ferrer from Bacolod) were very frugal with their only son. “He did not behave like he had everything in the world. I found him so refreshing, so completely without affectation. I fell in love,” said Mrs. Dans.

Totoy and Cheloy decided to get married in 1950; she was 20 years old. Father Delaney told the future Mrs. Dans: “In choosing a partner in life, the husband comes first, then the children, career comes last. Sustain the marriage by communicating constantly. Nurture it.” As Mrs. Dans' father walked her down the aisle, he whispered to her, “There is no advice I can give you. Whatever wrong your mother and I did, do not repeat, and your marriage will succeed.”

She had her first child at 23, followed by nine others within 11 years. At 34, Cheloy had 10 children and her doctor said that she could bear another 10. She blanched and said, “Twenty children? They'll become juvenile delinquents!"

“Shawl of the Innocents” (2009) Acrylic on Canvas

Artwork images from the artist’s collection, courtesy of Ayala Museum

She is amazed when people say it is difficult to raise children. “I played with them; breastfed all of them. During those times, there were no disposable diapers, no washing machines. Every now and then I had household help. There was no floor polisher, no microwave, no computers, no TV, no dressed chicken! My mother would kill the chicken for me. And I cooked a lot, especially for my teenagers who had bottomless pits.”

She remembered one particular mealtime when the grown kids talked about how many of them ran away from home during their rebellious teen years. One by one, seven of them raised their hands. The eighth said, “I also ran away, but no one noticed.”

“All the challenges in my youth have added to my wisdom as a mother, an artist and a grandma.”

Mrs. Dans also laughingly recalled the time she was busy painting in her studio when her daughter barged in to apologize, saying, “Mommy, I'm sorry, I drove your jeep without permission.” “Why?” she asked, not looking up from her work. The daughter answered, “I went to the hospital.” Still not looking up, she asked absent-mindedly, “Why? Are you sick?” “No,” her daughter said. “I had a pregnancy test, and it's positive.” That was when Mrs. Dans made a mistake with her brush stroke. She sat down with her daughter and they had their talk. She found out the latter did not love her boyfriend enough to marry him. Mrs. Dans did not insist, saying, “So don't get married.”

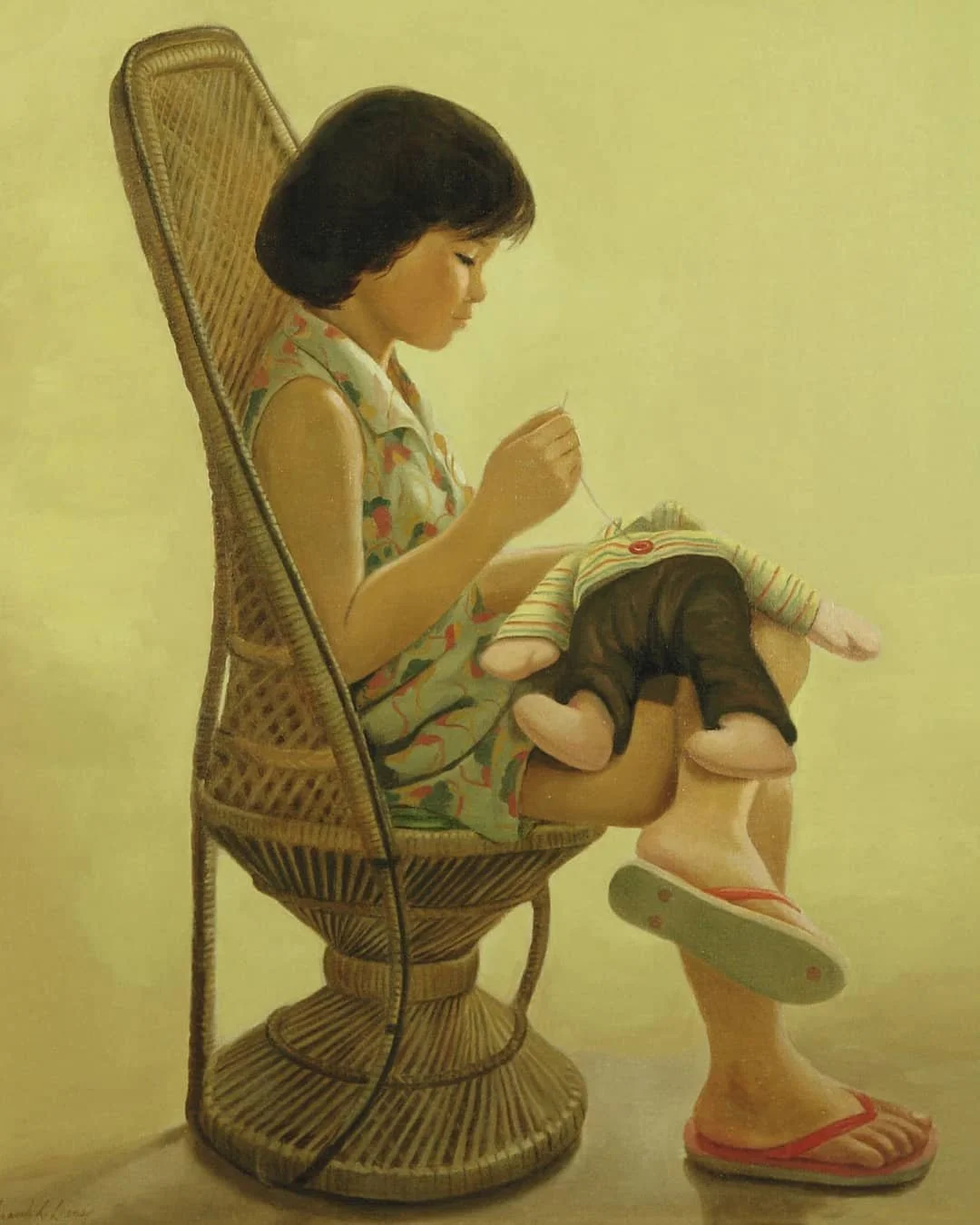

“Barbra” (1976), Oil on Canvas, Barbra Dans Collection

Artwork images from the artist’s collection, courtesy of Ayala Museum

Mrs. Dans still hosts Sunday dinners with her children, their spouses and grandchildren who live in Metro Manila. The others are in Los Baños, Singapore and the U.S. Her cook would call them to confirm how many are coming for dinner and report to Mrs. Dans, “Ma'am, 40 only.” Mrs. Dans has thirty grandchildren and six great-grandchildren, with a seventh due in July. “And my grandkids are six footers,” she added.

She now says that her early years of marriage and motherhood were a struggle to keep the family whole. “We had our own squabbles. One of things that kept our marriage strong was Totoy and I learned to love each other. All I did was serve, serve, serve. I'm harvesting now. I have peace and quiet. All the challenges in my youth have added to my wisdom as a mother, an artist and a grandma. Without the texture of what I went through, I wouldn't be the person I am now.” For the first time, she can choose how and where to spend her day. Usually, she is in her air-conditioned studio that looks out to a lush garden that's evergreen, no matter what time of year.

In the course of this interview, she'd pause in the middle of a sentence and turn towards the clear wide window, saying, “Sorry, I keep getting distracted. Look at those maya birds on my hanging plants. They're a family. They nest here.” And when she waves good-bye to me, it comes with a “teacherly” admonition and a smile, “Stop calling me Mrs. Dans! Tita Cheloy will do.”