Soft Exile Comes Home

In “Narito, Naroon,” Sa Tahanan Co. reframes Filipino migration as a condition of soft exile

Words Randolf Maala-Resueño

Photos courtesy of Martina Reyes

February 09, 2026

At Art Fair Philippines 2026, Sa Tahanan Co. arrived as a careful comeback. Their project “Narito, Naroon” asked what it meant to be Filipino when your life has been shaped by distance, airports, remittances, and the quiet ache of family video calls.

For co-curator Anna Bernice delos Reyes, now based in Berlin, the exhibition was both a homecoming and a critical mirror.

“We use the term soft exile,” she said, “because our leaving is personal, but structurally it is colonial.” The show did not romanticize diaspora. Instead, it situates migration as a legacy of empire, labor export, and state neglect that many Filipino families know intimately through OFW histories.

Home as archive, body as territory

‘The Model Family Award’ by Lizza May David

“Home is not just a house,” delos Reyes reflected. “For many of us who move constantly, our body becomes the archive.”

This idea animated the spatial logic of the exhibition. Rather than guiding viewers along a fixed path, the curators allowed wandering, lingering, and returning.

Audiences drifted between fabrics, images, videos, and objects that felt like fragments of memory carried across borders. Many visitors paused longer than expected, as if recognizing their own family histories inside unfamiliar artworks.

Works that carry heat, flight, and rupture

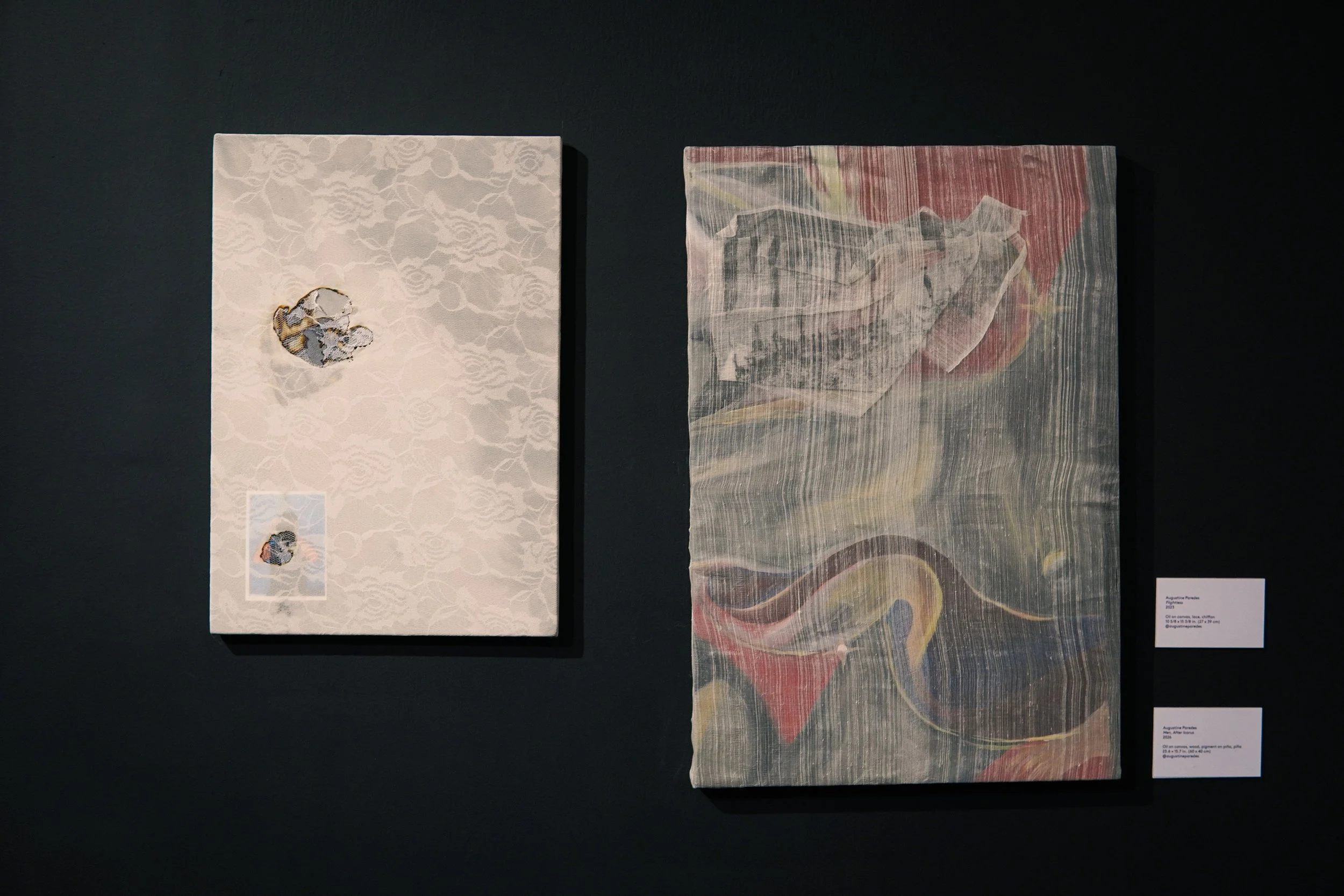

‘Flightless’ and ‘Men, After Icarus’ by Augustine Paredes

Augustine Paredes’ paintings anchored the show in myth and history at once. In ‘Flightless’ (2023), oil, lace, and chiffon cling to the canvas like skin remembering a fall. The delicate textiles soften the violence of Icarus while suggesting the fragility of migrant aspiration.

In ‘Men, After Icarus’ (2026), Paredes layered oil with pigment on piña, placing Japanese men in 1940s Mindanao behind the Icarus figure. The myth becomes a colonial backdrop, beauty and brutality braided together.

The works felt like “developing drafts,” as delos Reyes notes, still breathing, still unresolved, still asking who gets burned by history.

Nearby, Leon Leube’s ‘Thermal Runaway’ (Kiki-333) fused a second-hand sarong with a graphics-card shroud using heat transfer, sunscreen, and PVA.

The garment has travelled through tropical markets and European resale platforms, returning like a migrant object. Viewers leaned in to read its surfaces, feeling how digital labor, tropical heat, and migrant bodies share the same risk of overheating.

Archives, orchids, and the politics of silence

Mechanisms of Deception by Katie Revilla

Lizza May David’s ‘The Model Family Award’ (2008) confronted the spectacle of OFW sacrifice. Eight balikbayan boxes surround a looping video that reveals how the state and corporations celebrate separation as virtue. Many Filipino viewers linger in discomfort, recognizing their own families in the narrative.

Her photograph ‘On Surface’ (2012) remained quiet but just as political, asking how bodies become media where nation, memory, and power are inscribed.

Across the room, Katie Revilla’s ‘Mechanisms of Deception’ prints 1940s U.S. anti-Filipino propaganda onto orchids. The flowers seduced; the images wounded.

As delos Reyes explained, Revilla works directly with colonial archives that kept Filipino objects “sleeping in dark rooms,” stolen and unseen.

In the center wall stood Ariana Villegas’ 3D-printed shovel “Pala mula sa “Tabi Tabi Po.” Its blade echoed a school desk, its handle a crocodile tail, facing a termite mound—inviting fairgoers to destroy the punso. The gesture was not against nature, but against silent decay in Philippine education.

Performance, dialogue, and why we left

‘Weider Wir Damals’ (Just like Back Then) performance by Alvin Collantes

The exhibition culminated in Alvin Collantes’ performance ‘Weider Wir Damals’ (Just like Back Then). Their moving body became a living archive, stitching Philippine and German intimacies through breath, drag, and diasporic rhythm. Spectators watched as if witnessing memory in motion, neither fully here nor fully there.

Delos Reyes was clear about the politics beneath the poetry.

“Everywhere you go there are Filipinos, and that is beautiful,” she said, “but we must ask, why did we all have to leave?”

“Narito, Naroon” refused easy nostalgia. It staged a dialogue between stolen archives, migrating images, working bodies, and inherited silences.

By the end of the fair, Delos Reyes hoped that viewers leave not with answers, but with a sharper awareness that Filipino identity is dispersed, contested, and alive, carried most faithfully in the body that keeps moving, even when home feels impossibly far.