Peeking at Quiet Curtains

After its run at the 60th Venice Biennale, the Philippine Pavilion’s featured exhibition—created by artist Mark Salvatus and curated by Carlos Quijon, Jr.—returns to the Philippines.

Words Portia Placino

Photos courtesy of Wika Nadera and National Museum of the Philippines

January 23, 2026

Mark Salvatus and I both grew up in Lucban, Quezon, a town where rain falls almost constantly, rice fields once stretched like a living green tide, and fiestas mark the rhythm of the year with processions, drinking, and endless celebrations. Our childhoods unfolded amid the slow, deliberate rhythms of agrarian life—the gentle plod of carabaos in the paddies, the earthy scent of wet soil after constant rainfall, the sudden sparkle of water in a rice field reflecting the sun. Each corner of town held a memory—children playing along the streets and canals, neighbors gathering to eat and drink, elders recalling stories of generations past.

Yet even as these rhythms endured, Lucban was changing rapidly under the pressures of modernity. Tricycles increasingly replaced walking as the main mode of moving around town, carrying students, market-goers, and workers in a constant hum of motion. Cellphones appeared in the hands of children and teenagers, connecting our small town to a vast, invisible network beyond the mountains. Rice fields and coconut trees slowly disappeared as more subdivisions were built. The nearby university transformed the town into a crossroads of ideas, ambitions, and cultural collisions, drawing in students, faculty, and visitors, and shifting the social and intellectual landscape in ways both exciting and disorienting. The quiet hum quickly became a consistent noise.

Philippine Pavilion Homecoming Exhibition. Image courtesy of National Museum of the Philippines

Still, moving around in Lucban, the majestic and mystical Mount Banahaw looms—though often hidden under clouds and mist, as the constant rain frequently obscures its slopes. Amid the changes and environmental problems, this part of the Sierra Madre continues to dominate. It is said that the mountain only reveals itself to those it favors, a phenomenon that imbues it with a quiet, magical presence. Surrounding it are countless local beliefs—some speak of protection, others of spiritual guidance, and many carry stories passed down through generations. Mount Banahaw is ever-present, even when unseen—a mountain that anchors the imagination, memory, and identity of the town.

For Sa kabila ng tabing lamang sa panahong ito, Mark translates this mythic presence into the materiality of his installation, using fiberglass to recreate the mountain’s boulders. These sculpted boulders evoke the duality of the mountain itself—danger and salvation. Local lore tells that enormous boulders could spew out from the mountain and wreak destruction, yet Mount Banahaw is also seen as a guardian, keeping the town cool, sheltering and protecting those who live in its shadow. Atop the installative boulders, instruments from the local marching band intermittently produce sounds—sometimes predictable, sometimes sudden, echoing the rhythms of town life. Much like the band’s presence in Lucban, these sounds signal events significant to personal, cultural, or political life, reinforcing the connection between the installation, Mount Banahaw, and the lived experiences of the town.

Philippine Pavilion Homecoming Exhibition. Image courtesy of National Museum of the Philippines

Drawing insight from Apolinario de la Cruz, more popularly known as Hermano Pule, another figure deeply rooted in Lucban life—Mark looks into the complexities of heroism, local identity, and lived histories. Though Hermano Pule is recognized in national histories, Lucbanins feel a more intimate connection to him—he was born in the town, and his heroism is inseparable from a religious anchor that continues to shape local devotion and collective memory. The exhibition title itself—Sa kabila ng tabing lamang sa panahong ito / Waiting just behind the curtain of this age—is drawn from Hermano Pule’s correspondence, reflecting his contemplations and revolutionary fervor. In Mark’s work, references to Hermano Pule serve as a bridge between personal, local, and national histories—embedding Lucban’s stories in broader narratives of faith, resistance, and belonging.

For Sa kabila ng tabing lamang sa panahong ito, Mark turns his gaze to the history of Lucban itself, seeking stories that are rarely acknowledged in national narratives. While sweeping histories often emphasize grand events, political milestones, or heroic figures, they frequently overlook the intimacies, the layered textures, and the quiet heartbeat of everyday people. Mark instead delves into obscure local histories and family archives, tracing lives, rituals, and relationships that form the fabric of the town. The Salvatuses themselves, long-standing figures in Lucban, become both a lens and a thread through which these histories are revealed—personal, interconnected, and deeply rooted in place.

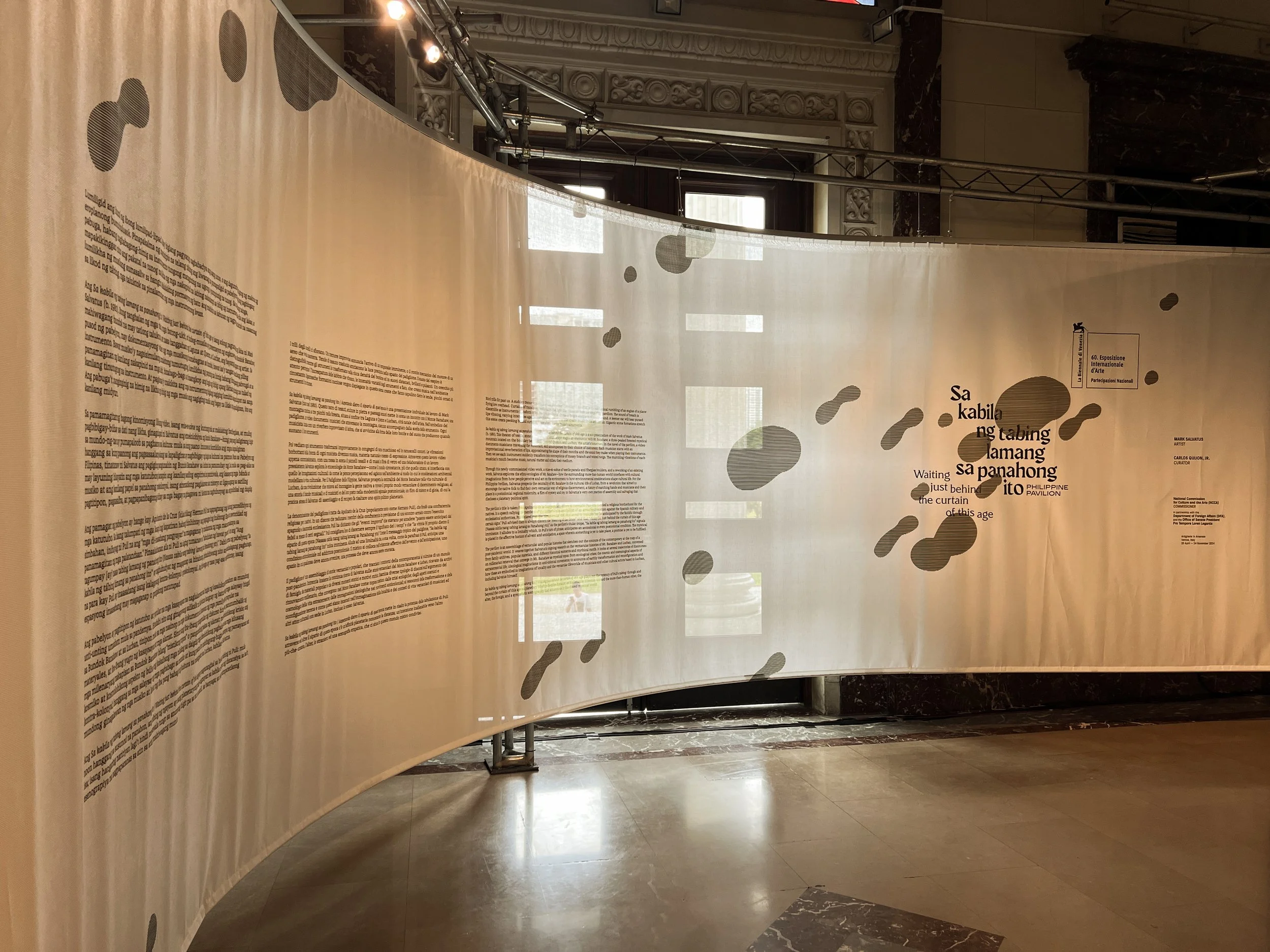

Installation view of Mark Salivates’ Sa kabila ng tabing lamang sa panahong ito / Waiting just behind the curtain of this age. Photo by Wika Nadera.

An essential thread in the tapestry of Lucban life is the local marching band, which punctuates every celebration, parade, and ritual. From the exuberant energy of town fiestas to solemn funeral processions, the band is a constant presence in the lived experiences of growing up in Lucban. Its music marks transitions—joy, grief, anticipation, remembrance—and serves as a communal rhythm, binding generations and creating a shared sonic landscape that accompanies childhood and adulthood alike. The band’s presence, like the rice fields, the rain, and Mount Banahaw itself, is inseparable from memory and identity, embedding sound into the very texture of everyday life.

Mark’s video work in Sa kabila ng tabing lamang sa panahong ito traverses the town, the rhythms of the marching band, and the slopes of Mount Banahaw, weaving together a Lucban rarely seen outside intimate memory. These are not the images of the town packaged for postcards or tourism brochures—they are moments of lived experience, unhurried, layered, and grounded in the textures of everyday life. Lucban is often known for the famous Pahiyas Festival, a riot of color, sound, and spectacle designed not only to celebrate harvest, but to attract visitors. The vibrancy of the festival is often emphasized in popular and touristic narratives, yet Mark’s lens turns elsewhere—to the quiet, to the rain-soaked streets, to the muted boulders, to the rhythms that persist outside of the performative gaiety. In this, the video work insists on a Lucban that is subtle, patient, and attentive—a Lucban whose quietness is as significant as its celebration.

Installation view of Mark Salivates’ Sa kabila ng tabing lamang sa panahong ito / Waiting just behind the curtain of this age. Photo by Wika Nadera.

This approach aligns with the decolonial sensibility of the Philippine Pavilion itself. Beyond the noise, the spectacle, the colorful tourist gaze, the installation foregrounds quiet, critical attention, inviting reflection on identity, place, and histories that are often overlooked or marginalized. Here, sounds emerge deliberately, intermittently, and with intention, signaling not only cultural and personal moments but also histories that exist between the cracks of dominant narratives. It is an invitation to pause, to notice, and to consider how Lucban—and by extension, the Philippines—can be understood not only through what is celebrated, but through what persists quietly—in family archives, in the shadows of Mount Banahaw, in the communal cadence of the marching band. In this tension between the visible and the hidden, the spectacle and the quotidian, Mark’s work offers a poetic and critical re-mapping of place, memory, and belonging.

In exploring Lucban through this lens, the Philippine Pavilion positions itself against the grain of spectacle-driven representation, privileging instead the slow accumulation of memory, reflection, and local specificity. It is a work that asks us to look and listen—to the rain, to the footsteps on muddy paths, to the intermittent calls of instruments, to the stories embedded in family archives. It asks us to see beyond the bright, performative colors of festival and tourism, into the subtle cadences of everyday life, where identity, history, and being are negotiated quietly, critically, and with nuance.

Installation view of Mark Salivates’ Sa kabila ng tabing lamang sa panahong ito / Waiting just behind the curtain of this age. Photo by Wika Nadera.

Ultimately, Mark’s installation in Sa kabila ng tabing lamang sa panahong ito / Waiting just behind the curtain of this age, curated by Carlos Quijon, is a meditation on time, memory, and place—on how towns like Lucban resist simplification, how local histories persist in the shadows of national narratives, and how even the quietest presences—the sound of a marching band, the misted outline of Mount Banahaw, the stories of families like the Salvatuses—shape collective imagination and cultural consciousness. It is an invitation to step beyond spectacle, to inhabit a Lucban that is intimate, layered, and resonant—a Lucban that continues to live, breathe, and speak in both seen and unseen ways.

The homecoming exhibition Sa kabila ng tabing lamang sa panahong ito / Waiting just behind the curtain of this age is now on view at the Marble Hall of the National Museum of Anthropology within the National Museum of the Philippines Complex. The exhibition runs until January 26, 2026. The artworks are on loan from the collection of National Commission for Culture and the Arts – Philippine Arts in Venice Biennale (NCCA–PAVB).