Collaging Attitudes

With text artist Lui Alcazaren, the visceral, raw emotions unpack when everyday packaging turns into loud, recycled thoughts.

Words Randolf Maala-Resueño

Photos courtesy of Lui Alcazaren

October 05, 2025

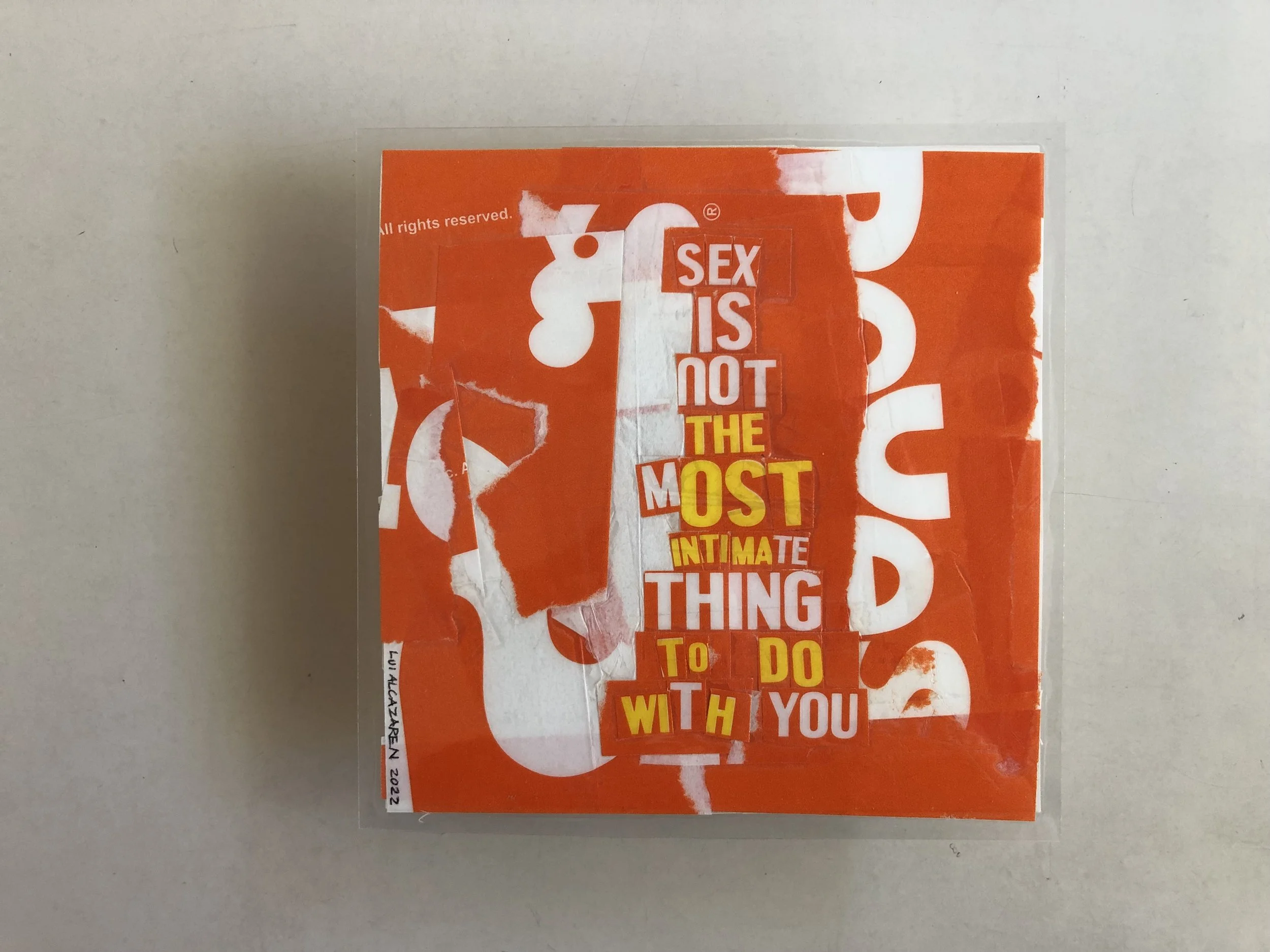

Camp, sex, and dark humorous transfixation–themes of daily babble taped together to create the essence of an artwork itself: to provoke and to edge against banality.

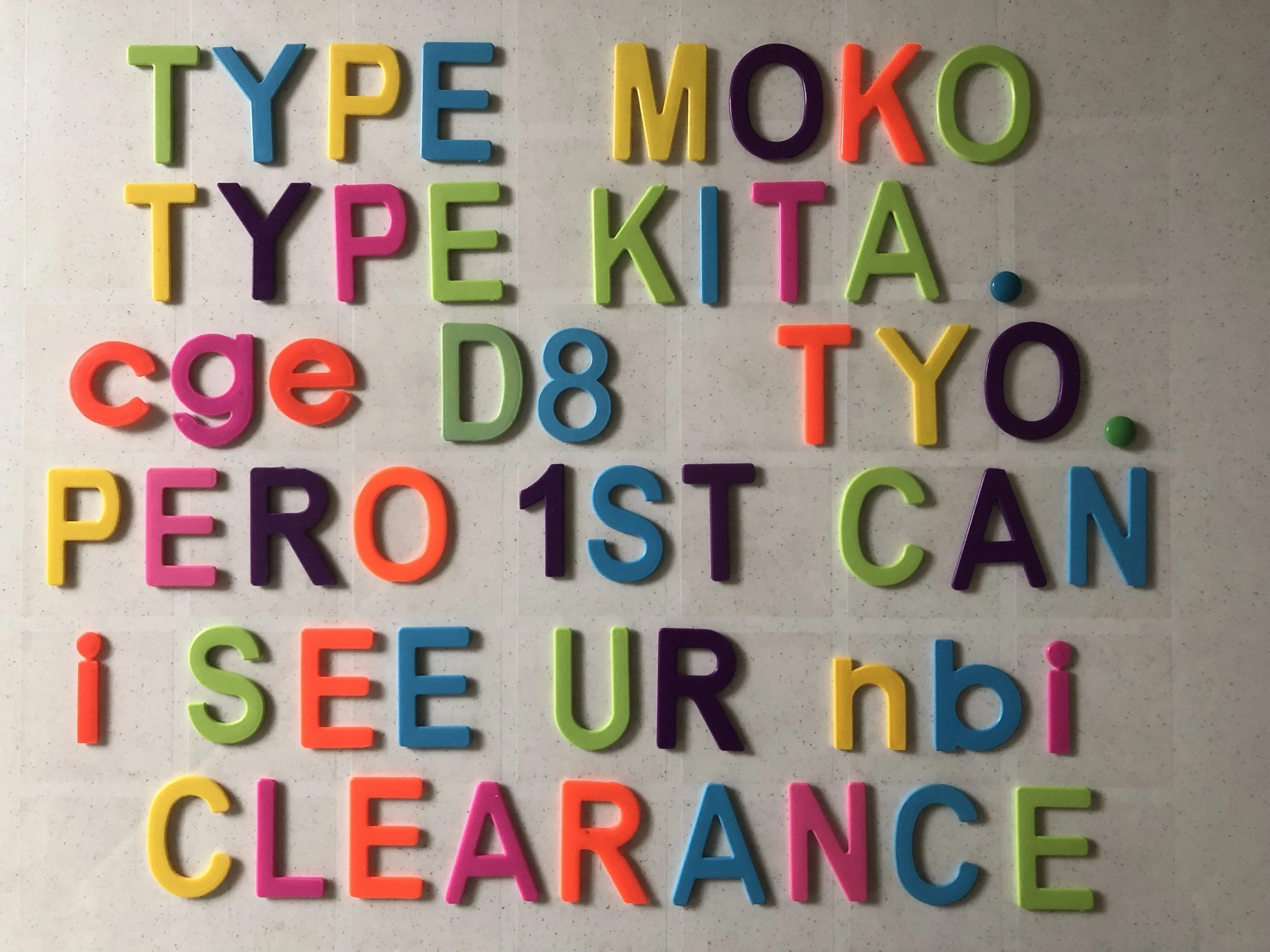

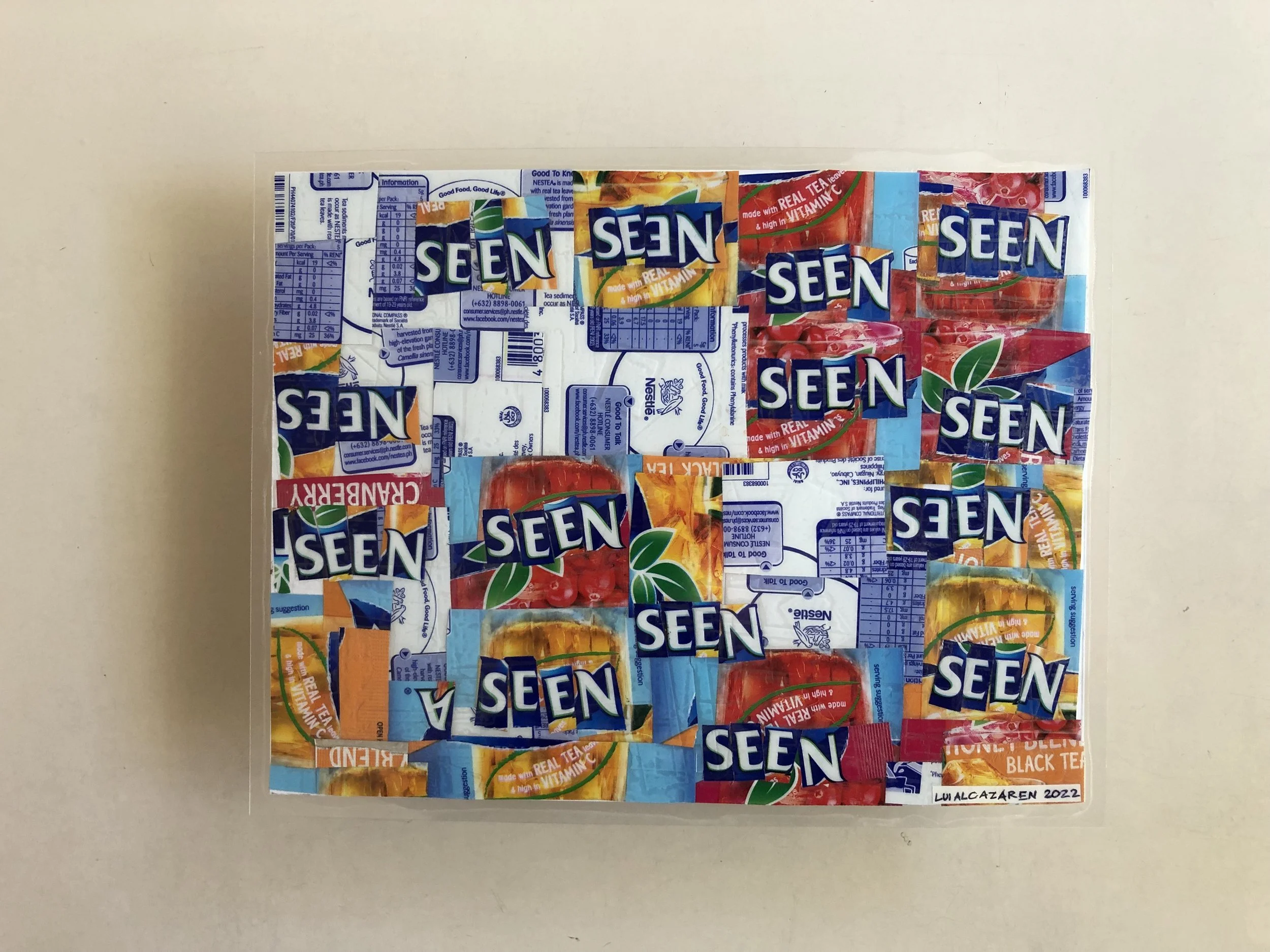

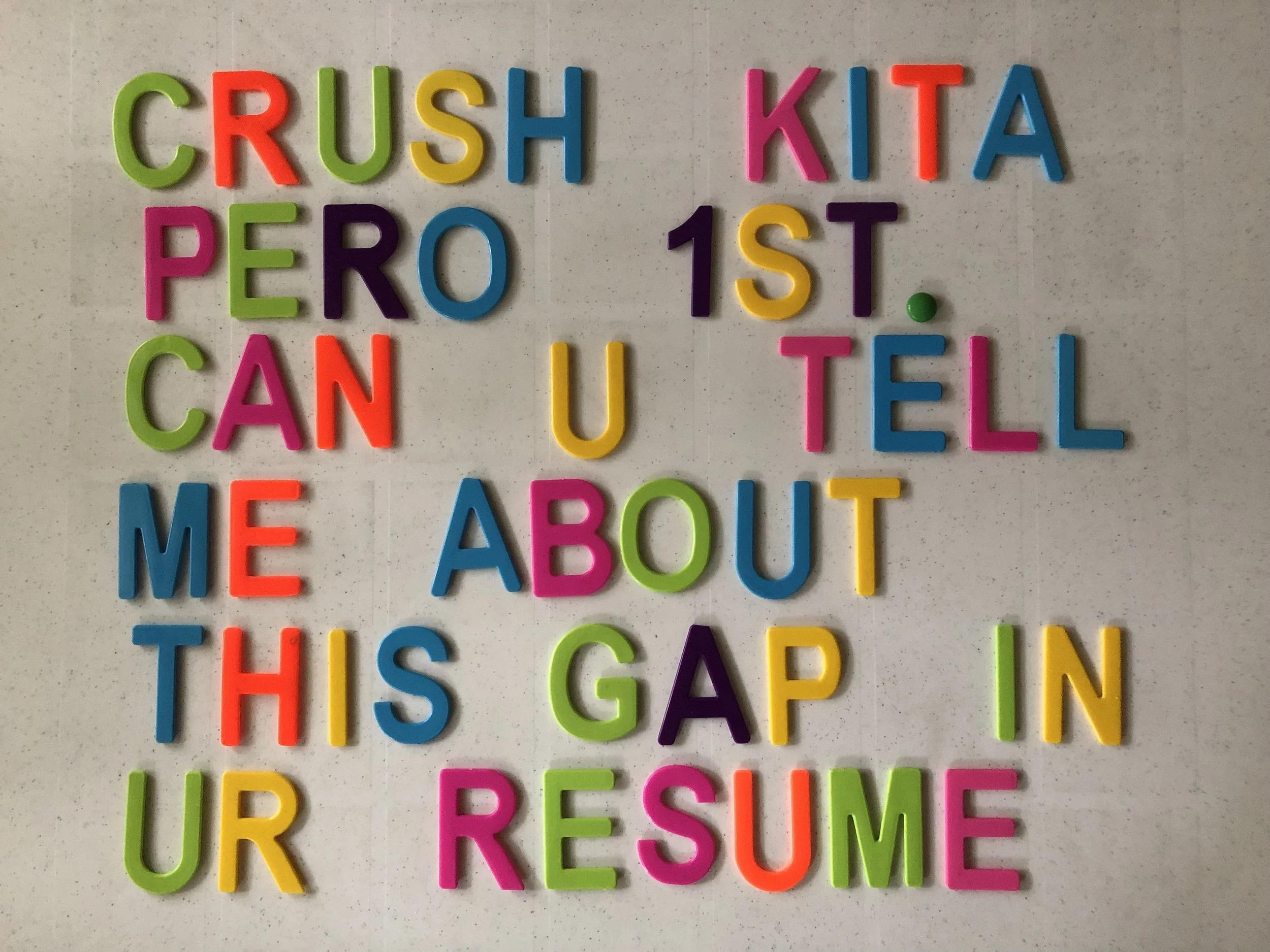

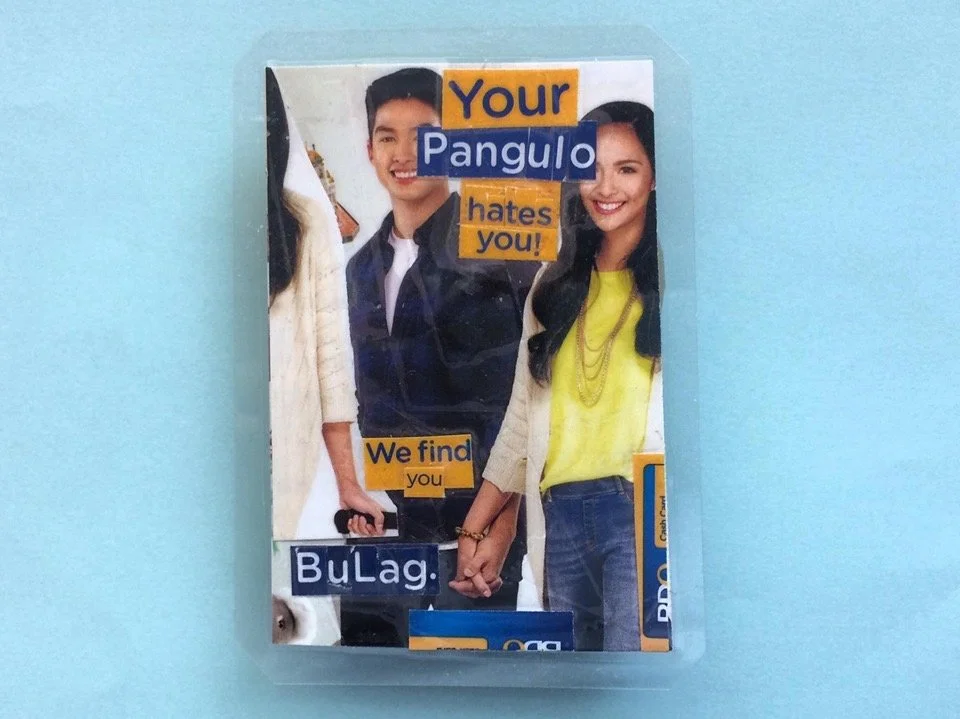

As mundane as they may be, these items, along with assorted brand packaging, litter collage artist Lui Alcazaren’s studio in Parañaque City. Scattered among them are rolls of scotch tape, torn magazine pages, children’s alphabet toys, and a quiet ambition for text-art recognition in the increasingly diluted visual art scene of the Philippines.

In this Art+ exclusive, we talked with the collage provocateur with a simple question in mind–why collage? And what’s the turning point for text art in the country?

Scraps, scissors, and a dream

The 35-year-old text-based artist has never shied away from the arts. After discovering graffiti and collage artworks in Thrasher Magazine at the age of 12, its grunge-esque aesthetic sparked Alcazaren’s curiosity and led him to its sister publication, Juxtapoz, an art and culture magazine. Inspired by its raw, expressive visuals, he channeled his artistic inclinations into studying industrial design.

While working as an industrial designer, Alcazaren explored other mediums, including sculpting and acrylic painting—creative detours that helped shape his evolving artistic identity. But in 2016, something clicked. It was collage and text-based art that truly resonated with him, a style that allowed him to “piece together” not just visuals, but an entire brand of his own.

Alcazaren’s process is straightforward: acquire his materials (much of which are recycled and basically free), pull up a phrase, collage cut up letters, tape it, take a picture, and post (or even sell). And yet, it’s more than the snips and the layers.

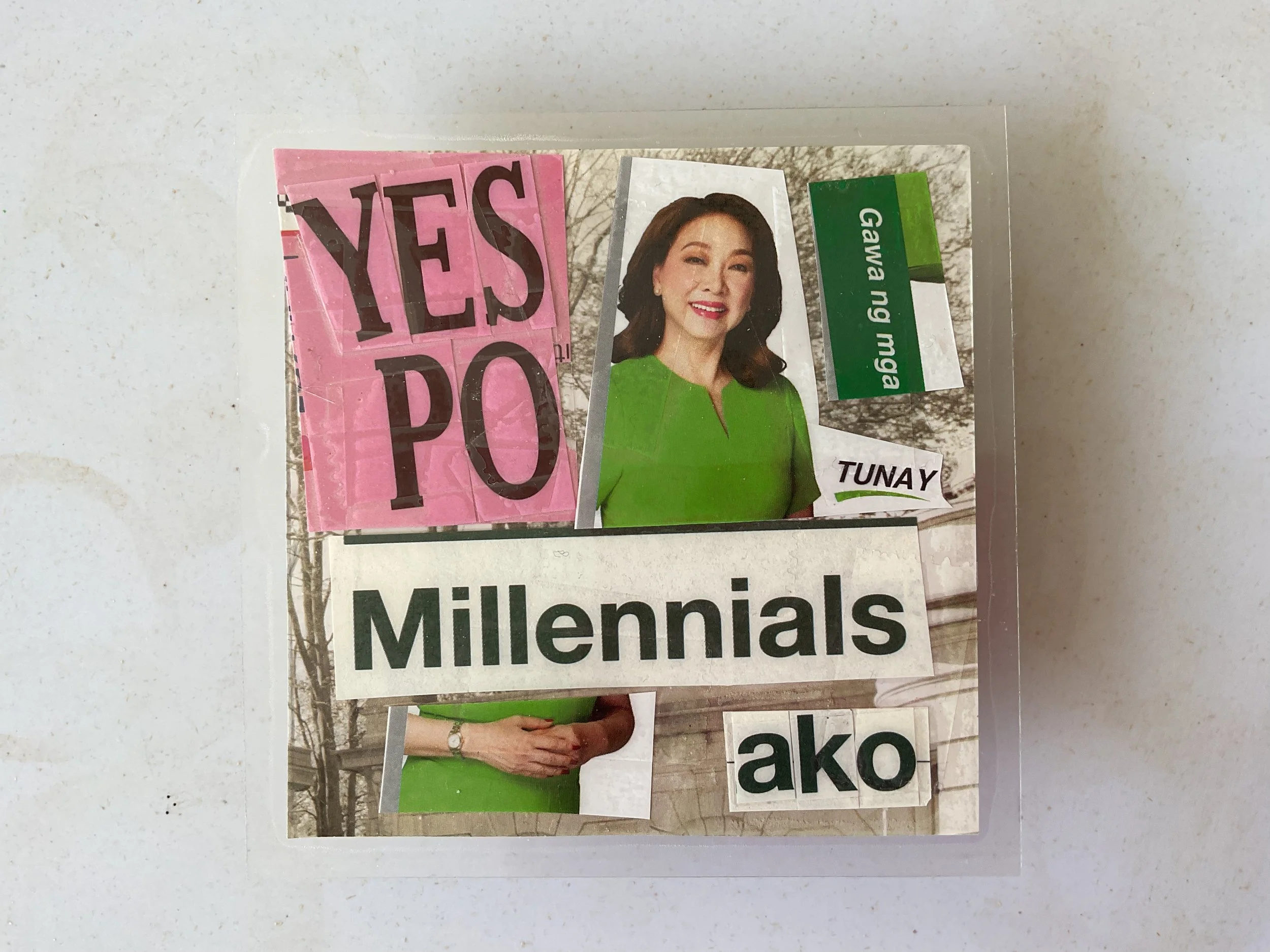

Collaging has to have an attitude. Alcazaren couldn’t have said it better: “As cocky as it sounds, I think there are things I say in my art that not a lot of artists can mimic. I think the voice of my art is the voice of a sincere, angry, Filipino millennial.” Accumulated frustrations mixed with an irreverent outlook against the artistic status quo drive Alcazaren’s narrative for his art.

In retrospect, his work is a masterful collision of pop culture, consumerism, expository, and language. Some were satirical, poking fun at relationship struggles and the woes of human existence. Mostly, though polarizing, features profanity, niche references, and sexual innuendos–a deeper dive into the camp portrayals of the Filipino experience.

“These things I say are from my daily life. Sometimes the inspiration comes from overhearing people; sometimes I just want to see what are the things I can and can’t say. I like to say things that are specific to my life,” he added.

It is a humor that is biting, catchy, and purposeful. Lines you wouldn’t necessarily mention in a social setting. An art form that is packaged to be unsettling yet profoundly relatable. This attitude is central to Alacazaren’s work; he mentioned, megaphoning his journey in finding his ‘voice.’

“The humor in my art comes from everyday life. I curse about specific Filipino issues. I make art about my [removed] gallbladder. I make art about being a middle child. I make art about Korean dramas I watch. Humor makes me and my art relatable–it's why people notice my art,” he remarked.

Reactions to his pieces vary across audiences, but Filipino purveyors, he said, feel more personal, drawing amusement from his “naughty, angry, and silly” Taglish colloquialisms on his diptychs.

“I think that’s my edge from other artists. I want people—when they see my art—to say that these were obviously made by a Filipino who grew up in the Philippines.”

Expanding the comfort zone

In the lengths of recognizing text-based artists in the industry, Alcazaren situates himself as an outsider still. He described the contemporary Filipino art scene as an “exclusive club,” where art galleries patronize certain types of art more than others.

“I am active in the art scene, but maybe just not so much in the art gallery aspect of it. And I am at peace with that. At the end of the day, as long as people buy my artworks, I'm all good.”

Grounded in hope, Alcazaren ultimately hopes for a simple legacy: to be regarded for his existence as a text-based artist, and for future creatives to fathom the many ways to be an artist.

Collaborations are on the way, he added, noting a focus for his group exhibitions with Manila Collage Collective, a collage community established in 2020. And with a proclivity for exploration, Alcazaren now dabbles in other text-based mediums, including neon signs, Microsoft Word, and latex paint, to name a few.

‘Recycling’ thoughts

In a country where the irreverent is political and the political is entertaining, Alcazaren goes for the jugular–a punch to the art scene’s interpretation of the form. His works lie in this intersection, recycling what’s discarded and creating something that shakes the contemporary art scene.

Lui’s works remind us that life is never fixed; it can be cut, rearranged, and given a new meaning. Maybe that’s its wonder, a provocative reclamation of art and language as a shifting medium–political, entertaining, and unapologetically Filipino.