The Little that is Left

On mapping the current state of Philippine material heritage.

Words Betty Uy-Regala

October x, 2024

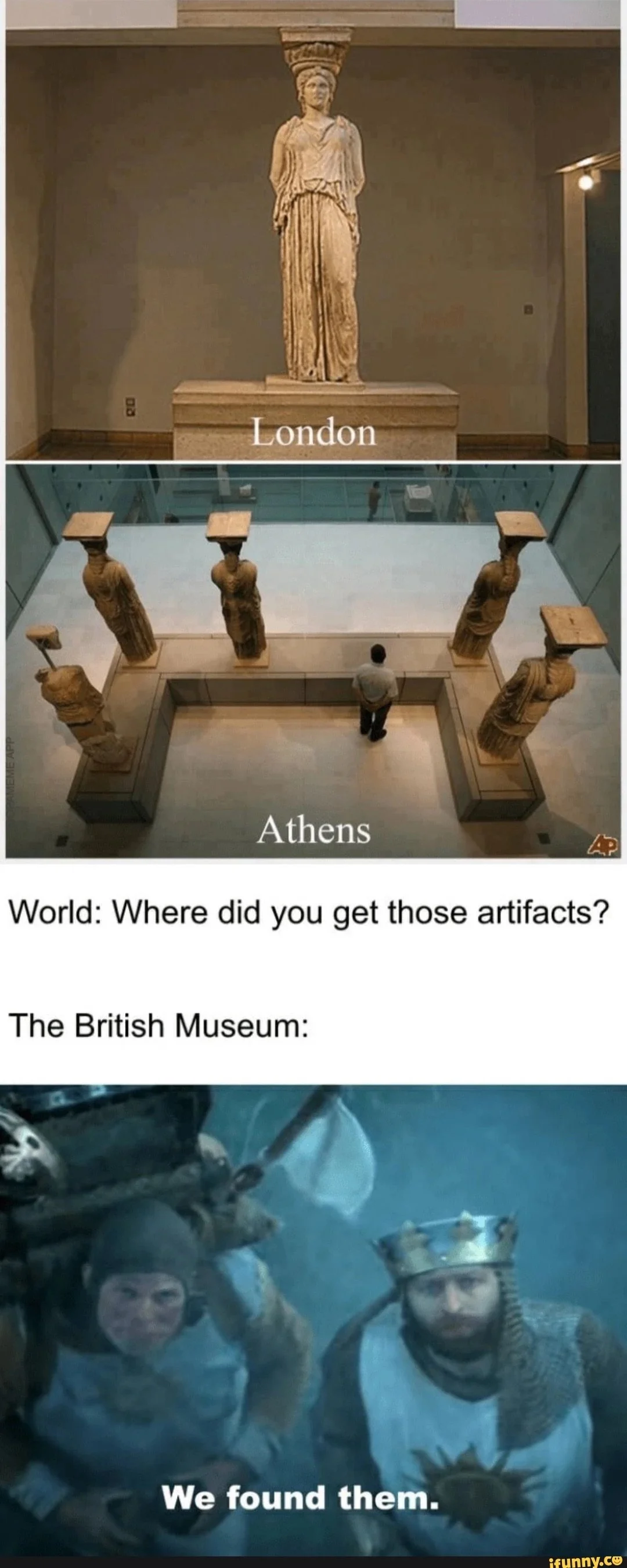

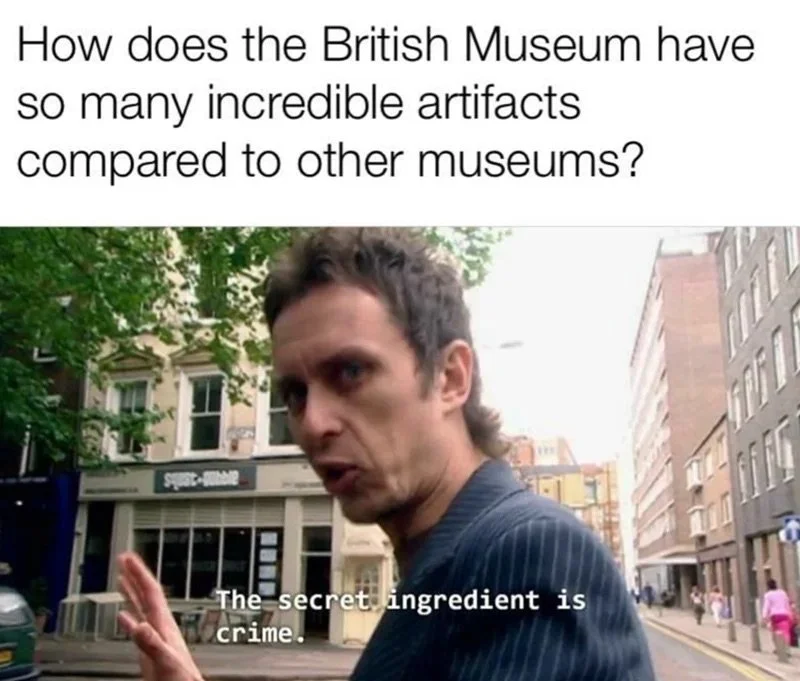

Humorous memes about the British Museum appearing on social media feeds capture a truth about its artifacts’ collection. Here are samples:

1. World: Where did you get those artifacts?

The British Museum: We found them.

2. How does the British Museum have so many incredible artifacts compared to other museums?

The secret ingredient is crime.

The British invaded Manila and Cavite from 1762 to 1764 during the Spanish colonial period. In the Mapping Philippine Material Culture (MPMC) site (https://philippinestudies.uk/mapping/charts), only six pages appear when a search is done for the British Museum.

The Mapping Philippine Material Culture (MPMC) site, a digital database project launched in 2021, houses a visual inventory and textual information of Philippine objects held by museums and private collectors outside the country. To date, the project has mapped 8,235 items. It’s a case of we don’t know what we don’t know, but we do know that there are a lot of Philippine cultural objects in state and private collections abroad.

The six pages that appear for the British Museum search yield a low of 72 Philippine cultural objects that are in the British Museum storage, or have passed through its doors, while a few are on display like the Moro Armour or the kurab-a-kulang. With a documented acquisition year of 1876, the armor is described as fashioned from the plates of water buffalo (carabao) horn held by brass chainmail and silver clasps.

Moro Armour

The MPMC site is led by Dr. Maria Cristina Juan, project head for the Philippine Studies at the School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS) at the University of London, together with Marian Pastor Roces, the project’s co-editor and lead curator for the project’s digital exhibits.

Marian Pastor Roces during the AFM lecture

Alliance Française de Manille recently organized a lecture by Pastor Roces titled “Philippine Artefacts in Foreign Lands and Possibilities of Rematriation” as part of the activities’ series for its Trajectories and Movements of Filipino People exhibition, which opened on August 31, 2024 and ended on September 21, 2024.

Like a robbery aftermath in a contemporary setting, a list is made to record the missing objects and their corresponding monetary value in a police report, which is a surface comparison to what the site is doing—taking stock of what was lost and where they are now. And in this instance, the police are the meme makers, the Filipinos, Dr. Juan, Pastor Roces, and the people of the world who are collectively putting pressure on the colonizers’ state collections.

Marian Pastor Roces via Facebook

“We don’t see them (diasporic objects) because they’re not here. The material culture heritage of the Philippines is, in large measure, overseas. Filipinos do not have access to much of the material evidence of our heritage. This is a kind of digging,” Pastor Roces said. Pastor Roces presented five factors which resulted in the dismal state of the country’s artifacts:

- These were taken out of the country as “souvenirs” during the 333-year Spanish colonial rule, the 48-year American colonial period, (not to mention the relative short invasions of the British and Japanese);

- These were included in scientific and pseudoscientific expeditions in the 18th and 19th centuries;

- These were placed in American modern science expeditions in the early 20th century;

- These were traded as antiquities which peaked in the 1970s and 1980s;

- The little that is left was trafficked—a reality that persists until today.

Marian Pastor Roces during the AFM lecture

She laid out three other circumstances that further exacerbated the current state of Philippine material heritage. The Battle of Manila during the Second World War in February 1945 destroyed almost the entire national collections in the Legislative Building and the Bureau of Science Building of the National Museum. Material culture studies were not deemed as significant post-war. Material culture collections started as an activity only in the 1970s.

But not all is lost. The Museo ng Kaalamang Katutubo, for one, is successfully collating the Philippines’ reference collection for ethnographic materials. The Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas (BSP) and the Ayala Museum are respective stewards of archeological gold jewelry collections.

Incidentally the BSP and the Ayala Museum have a joint exhibit at the latter location titled Reuniting the Surigao Treasure, which showcases 38 various gold objects from the pre-colonial period. The exhibit was opened on May 16, 2024 and will run until 2027.

Partial to little things, the lecturer preambled her talk with a gold anthropomorphic figurine traced to Suyoc valley in northern Benguet. The figurine has a recorded acquisition date of 1850 by German chemist and ethnographer Alexander Schadenberg (1851-1896), who intermittently voyaged to the Philippines from 1879 to 1885.

Anthropomorphic figure

Upon Schadenberg’s death, his collections were placed in museums in Berlin, Dresden, Leyden, and Vienna. The figurine is kept in storage at the Museum of Ethnology in Vienna. The figurine is believed to be associated with fertility given the erect phallus, which portends prosperity.

While the process of mapping Philippine artifacts is a crucial initial step, there is still the undertaking of recovery or a return of these cultural objects to the country.

Pastor Roces believes that the trend of repatriation will continue. Emmanuel Macron, the president of France, committed to return 26 cultural objects to Benin, a country in West Africa in 2017. Two years later, it released a timetable following criticisms for not following through with his promise. In the Philippines, the American government returned the Balangiga bells to the country in 2018 after 117 years.

The speaker proffered an alternative to repatriation (which happens when a state deals with another state for the return of cultural items)—rematriation. To illustrate what rematriation in this context means, she told the story of Billie Riley, a British national, who was a volunteer teacher with the Santa Cruz Mission in Lake Sebu, South Cotabato from 1978 to 1980. She lived amongst the Tboli.

Billie Riley from the Gónô Tmutul Building a House of Stories trailer

During his stay, the Tboli gifted him with an assortment of tools, jewelry, and other cultural objects. When he turned 70 years old, he thought of returning the cultural objects to Lake Sebu and joined the group of Pastor Roces in April 2023. Riley turned over the cultural gifts to him to Benjie Manuel, a Tboli Sbu Senior High School head teacher.

Pastor Roces concludes her lecture by saying that there is no template for rematriation as of the moment. However, the general idea behind it is that the cultural objects outside the country of their origin are returned to the community itself like how Riley returned the cultural gifts to the Tboli community.

As for the British Museum, an explanation is given for the contested artifacts in the About Us section of its website: “Objects have been acquired in a variety of ways. Some objects are subject to questions about, or requests for, return to other countries. Statements on the most frequent requests and information on the current status of the discussions can be found below.”