Stories with Meaning

Rodel Tapaya and Marina Cruz built a creative oasis outside of their regular art careers. Now, they’re sharing it with fellow artists and the bigger community.

Words Pao Vergara

August 21, 2024

Tucked away in a quiet suburb north of Metro Manila, amidst Guiguinto, Bulacan’s sprawling rice fields marking the beginning of the Central Luzon Plains lies what could be the next community creative center: IsTorya Studios, built by artists Rodel Tapaya and Marina Cruz.

IsTorya is spelled so because Tapaya and Cruz want to focus on the word torya, which is Filipino for ‘meaning’ or ‘substance,’ “mga istorya na may torya (stories with meaning),” as Tapaya puts it.

“Are you familiar with the word?” Tapaya, who graduated from the University of the Philippines with Cruz in the early 2000s, asks.

“I think my grandparents used it, but my friends and I, not much,” I sheepishly grin, preparing to laugh with a “you English-speaking kids” joke which doesn’t arrive.

IsTorya Studios office. Photo by Pao Vergara

Cruz, meanwhile, is teaching a workshop as I interview her husband—the hustle and bustle of inquisitive activity blending well with an already lively interview.

It quite literally started at home. Board games, a regular fixture for the couple and their three children, became even more of a bonding venue during the pandemic. At one point, Tapaya saw one of his sons designing his own board game, mechanics and all, and the painter, active for more than two decades now, was touched, telling himself, “Wow, that was me when I was young, curious, building, unconstrained.”

Moved by this moment (the prototype remains on display by the Studio’s window), Tapaya and Cruz, who also comes from a family of educators and who was herself an art teacher at one point, proceeded to make board games based on Philippine History, which served the dual purpose of not only entertaining their kids, but educating them too.

IsTorya, the narrative dasign studio, is the brainchild of Rodel Tapaya and Marina Cruz.

Thankfully, its entertainment value proved itself and the collaborators realized that the games they just invented, Patandaan and Sangangdaan, could be shared. They playtested these with friends, and when the feedback was encouraging, the next playtesting was with school teachers, who, in turn, also gave positive feedback.

“Our children are also homeschooled,” Tapaya shares, “there are certain aspects of history not taught or not taught enough in school. Biases come into play, and narratives get left out, especially those of the marginalized.” A 2019 report by the Commission on Audit revealed that many printed history textbooks circulated in schools had stark factual errors, including in social science and history subjects.

There were still lessons to be learned and improvements to be made, so Tapaya and Cruz further refined the two games, consulting historian Ambeth Ocampo in the process and releasing in mid-2022 the public versions of Patandaan and Sangandaan, which from board games became card games.

After steady sales, it was here that Tapaya and Cruz realized the narrative power of games as an educational and advocacy tool.

The time spent developing and refining the games also served as a break for the artists from their regular practice. Exercising creativity and focus in a field outside of their main occupation proved to help them paint better when they finally returned to their respective studios.

Seeing its value for themselves and others, they wanted to maintain this creative oasis and share it, thus a new project was born, the Tagpo series, which officially launched in Art Fair Philippines 2024 through the Fair’s Incubators program.

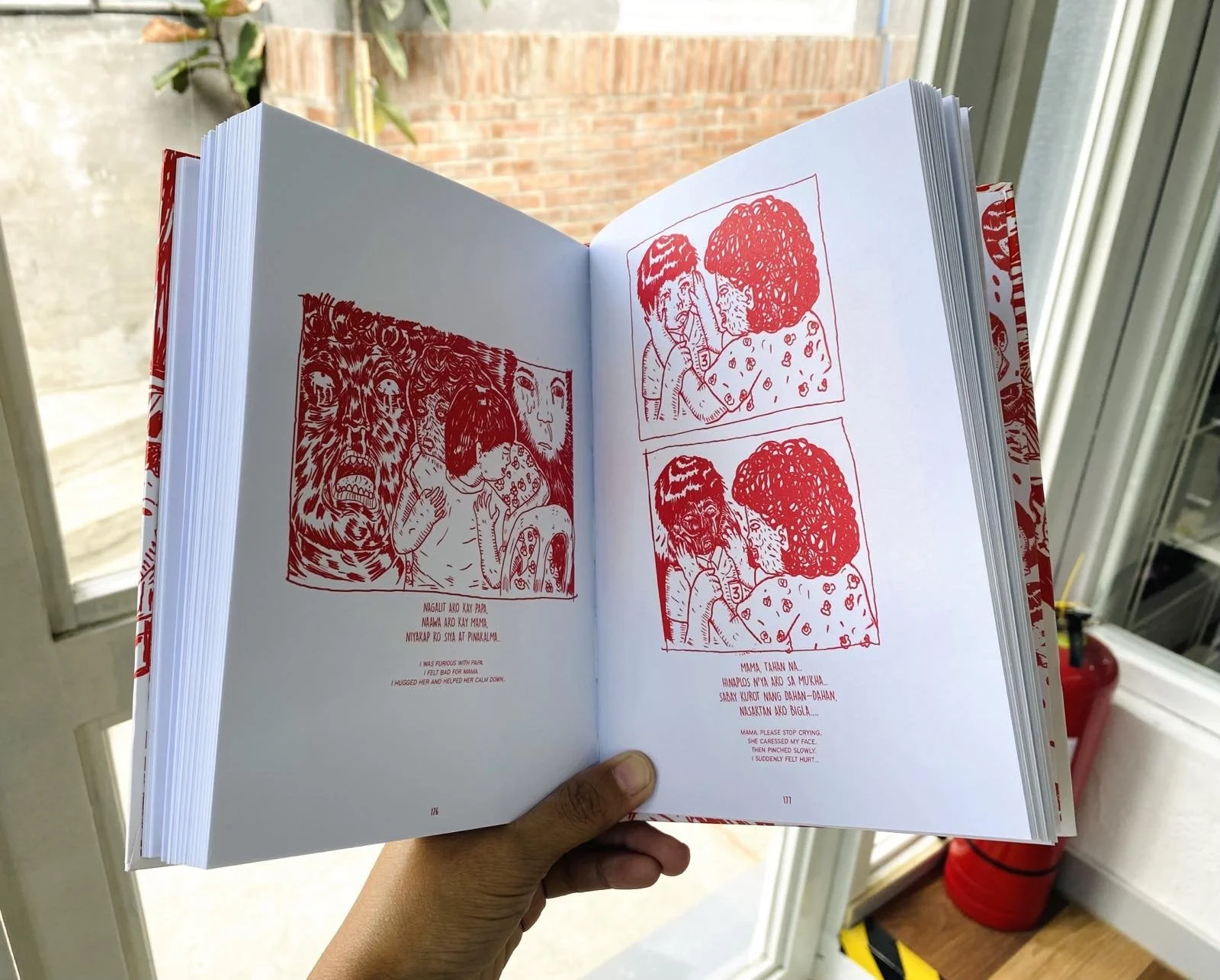

Tagpo is a book series where Tapaya and Cruz, as well as artist-friends Russel Trinidad (Doktor Karayom) and Archie Oclos, each released a visual novel-slash-art book. Despite being published books, it’s hard to exactly classify what literary genre each work in the series falls under.

Tagpo Story Collection

They’re not graphic novels in the traditional sense given the genre’s form and conventions, but they’re also not a collection of prints or an art book of standalone works, as each book has a cohesive narrative that each artist is sharing.

“I think of it as a canvas extended but also compressed,” Tapaya ponders as Cruz’s laughter echoes from across the hallway, “extended in that I have more space to tell a story I want to tell, but compressed in that literally, physically, it’s a lot smaller than a painting.”

Tapaya’s art-novel, in particular, is an extension of one of his paintings, featuring distinct characters and building on the universe hinted at in the original canvas.

Cruz’s book will also ring resonant bells with those who follow her work, as it features hyperrealistic portraits of old clothes, each with an essay or poem attached to it.

Trinidad’s story, meanwhile, is about the adventures and horrors of grade school life in past decades, all situated in a very Philippine context, while Oclos similarly tackles larger social issues, albeit through the lens of a coterie of street cats, echoing Natsume Soseki’s novel I Am a Cat.

Tagpo was incidentally the name of Tapaya’s first show after graduating, which he held in an unassuming shed somewhere in UP Diliman after major galleries declined his pitches. For reception food, they served kwek-kwek and other street food commonly found around town.

Aside from Tagpo, IsTorya studios has also published traditional graphic novels, some of which have been submitted. The Studio is open to pitches from the general public, “especially if the story is one that not many publishers might want to tell,” Tapaya explains.

IsTorya’s publications and games have also been carried and sold in diverse venues, both mainstream and independent, from Art in the Park to National Bookstore to Mount Cloud Bookstore in Baguio.

Indeed, aside from a Walden pond of the mind, IsTorya studios also serves as a vehicle for civic and community engagement as issues featured in both Tagpo and regular works include the assimilation of institutionalized children back into society, child abuse and rescue, as well as the neglect of transport workers and attempts to phase out their livelihoods, to name a few such advocacies.

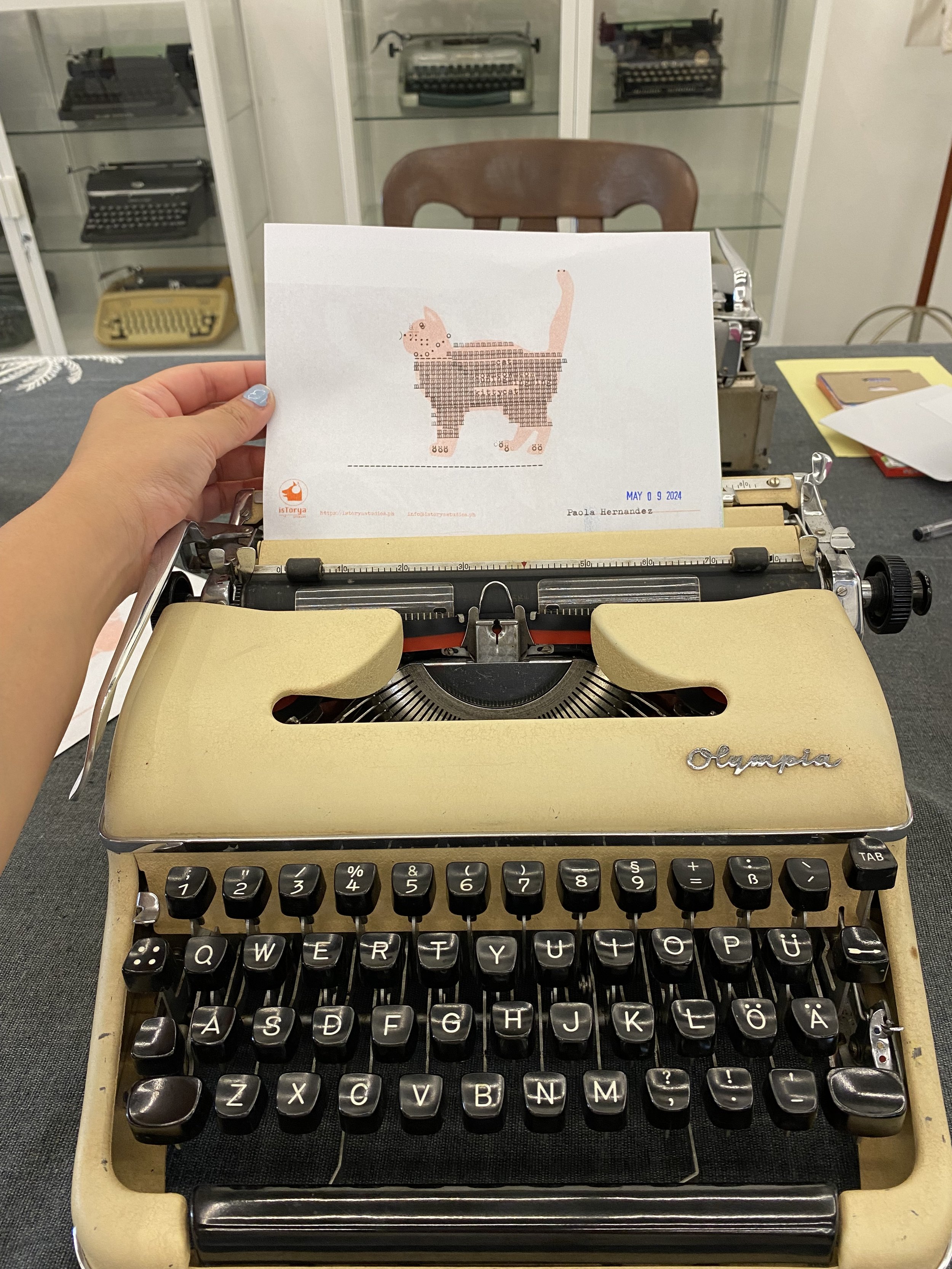

Recently, IsTorya studios held yoga classes and a typewriting therapy workshop using actual working typewriters from Cruz’s personal collection. The typewriters were also restored by some of the last typewriter repairers in old Manila. Aside from locals, many of the workshop’s visitors came from Pampanga province and Metro Manila.

Typewriting therapy workshop at Istorya Studios

Finally, despite disclaimers from the artists that the project is a hobby and break from work, Istorya Studios has managed to sustainably support its full-time employees, many of whom are locals from Bulacan.

The artists are confident that IsTorya Studios will eventually serve as a venue for community events, especially those related to creativity and advocacy, all with an element of tactility, apt for a touch-starved, terminally online, meaning-seeking milieu.

Stay updated via their website, http://istoryastudios.ph or follow them on their official social media channels, @IstoryaStudios on Facebook, YouTube, and Instagram.