Printmaking Offers a Wellspring of Possibilities in Vargas Museum’s ‘Parched earth, ardent spring’

The exhibition was best approached with conceptual groundwork only as a secondary concern. Instead, the medium took center stage, positioned by the exhibition as a “primary ground where ideas consistently and ardently spring.”

Written by Chesca Santiago

June 13, 2023

Situated between framed prints, the flowing expanse of Ronyel Compra’s luta sa balay ni Masyang (center) was impossible to miss.

Printmaking has had its skeptics. We could name the reasons why print has garnered cynics of its artistic validity: its historical affinity with reproductions, the mechanical nature of its process, or simply just because it’s not painting or sculpture.

But in the Philippines, the historical and contemporary vividness of the printmaking scene will uphold that print is – as it is and has always been – an art form. In partnership with Tin-aw Art Projects, the UP Vargas Museum’s recently concluded Parched earth, ardent spring is the medium’s most resounding affirmation today. The exhibition featured 11 printmakers and presented works spanning from 1970-2023, lending a concise yet comprehensive art historical overview of the art of print in the Philippines.

From the exhibition notes, Parched earth, ardent spring sought to “[trace] concepts of the foundational across generations of Philippine visual artists and printmakers.” But the exhibition was best approached with conceptual groundwork only as secondary concern. Instead, the medium took center stage, positioned by the exhibition as a “primary ground where ideas consistently and ardently spring.”

Thus, from etching, linocut, serigraphy, viscosity color printing, woodcut, rubber cut, intaglio, to termite soil rubbings, Parched earth, ardent spring was a robust lineup of the forms and possibilities of print. Its attempts to expand the medium was most evidently, albeit disorientingly, seen in Ronyel Compra’s luta sa balay ni Masyang (2023), a print produced by the luta technique where the artist set termite soil on his grandmother’s home and rubbed it against textile. Placed along the museum entrance, its sheer size and location made it one of the first works that greeted exhibition visitors, effectively setting the boundary-breaking tones of the show.

As if to temper his highly experimental home archive, flanking Compra’s luta sa balay ni Masyang were more familiar formats of framed prints. Through etching and viscosity color printing, Ofelia Gelvezón-Tequi transposed Italian frescoes onto paper with Homage 2 (1987) and Homage 3 to Amrogio Lorenzetti (1990). Gelvezón-Tequi used Italian imageries to etch the Philippines’ own version of dictators and tyrants, making for a seamless cross-cultural intersection of subject and form. Imelda Cajipe-Endaya’s 1974 prints Buhol-Buhol and Kastigo similarly operated on social commentary, foregrounding class struggle and women’s rights through etching.

Ofelia Gelvezón-Tequi etched Philippine political crocodiles and skeletons onto paper.

Headless beings and a church-like structure articulate Imelda Cajipe-Endaya’s social commentary.

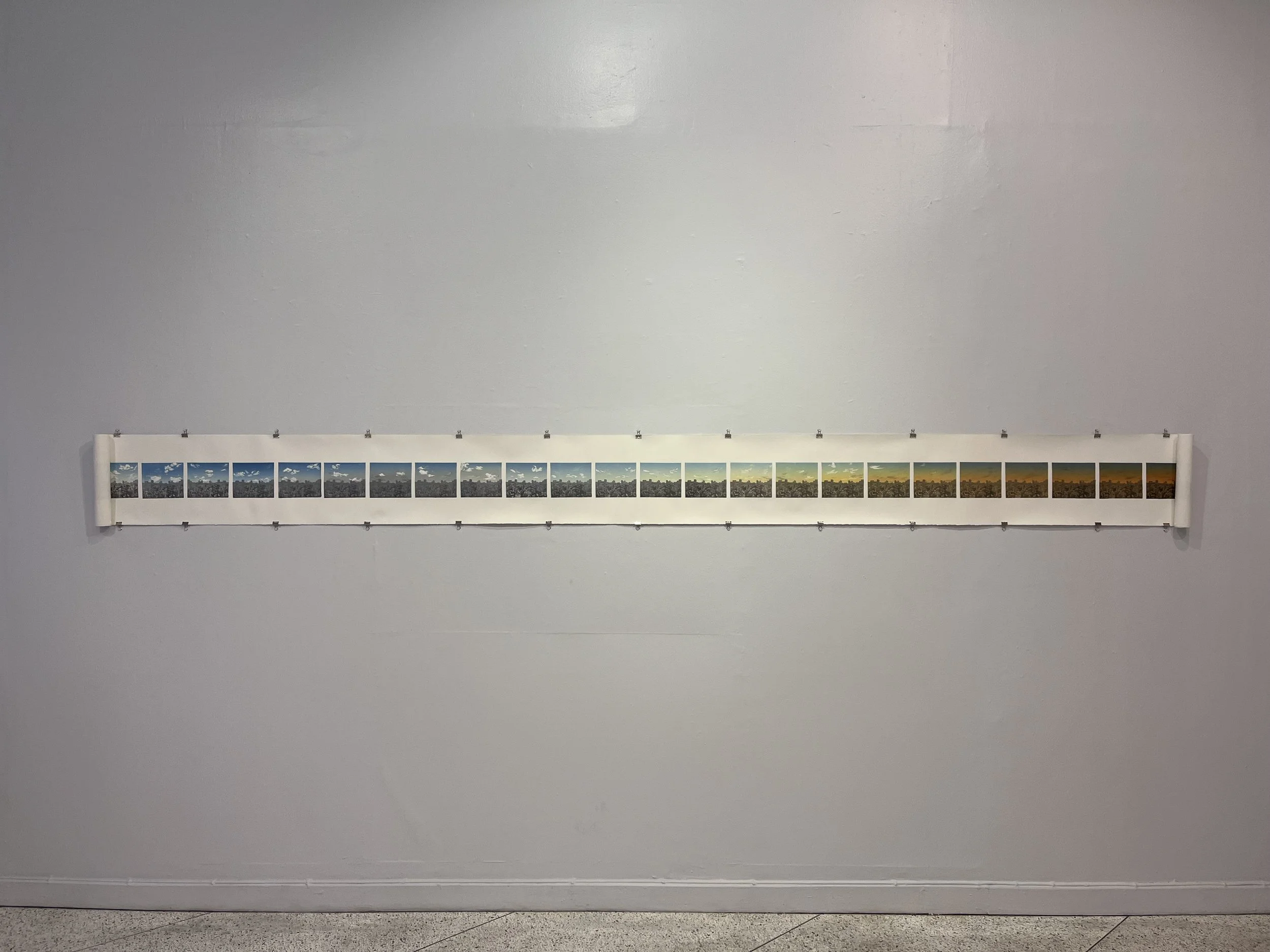

In another testament to the prospects of printmaking, Henrielle Baltazar Pagkaliwangan’s liminal space, unstill lives (sunset) (2023) was a drypoint on monotype scroll print of a cityscape chronicled from daylight to dusk. The work – dominating an entire wall of the museum, despite having been made with the artist’s precisely delicate lines – masterfully demonstrated Baltazar Pagkaliwangan’s draftmanship skills.

From daylight to dusk, rendered through Henrielle Baltazar Pagkaliwangan’s delicate draftmanship.

The adjacent room of the 1/F galleries was home to even more atypical prospects of the medium. Rey Concepcion worked with printed pages for his Last Of (2023) series, where he recreated the last pinwheel, paper boat, and paper plane in response to an anticipated extinction of print. Concepcion encased these in acrylic casts serigraphed with a declaration of the medium’s looming loss.

The acrylic encasing in Rey Concepcion’s Last Of series formed a parallel to the museum’s glass-panelled walls.

The exhibition showed a play on perspective, positioning works in strategic orientations, as with Compra’s and Concepcion’s works. However, the same can’t be said for Virgilio Aviado’s Miracle of Lipa (2023), an installation of petal-shaped prints suspended on mulberry scroll paper. Miracle of Lipa ended up being a one-dimensional viewing experience as seeing its totality was disrupted by the opaqueness of the scroll paper.

In an act of the artist’s devotion, Virgilio Aviado’s Miracle of Lipa (front) recreated the miraculous rain of petals in 1948 associated with the Lady of Mt. Carmel.

With only 11 printmakers in its roster, Parched earth, ardent spring was a well-rounded account of the development of printmaking in the Philippines—faithful to the art of print and expansive in its scope.

Parched earth, ardent spring ran from 11 May-7 June 2023 and featured works by Ambie Abaño, Virgilio Aviado, Imelda Cajipe-Endaya, Ronyel Compra, Rey Concepción, Brenda V. Fajardo, Ofelia Gelvezón-Téqui, Caroline Ongpin, Henrielle Baltazar Pagkaliwangan, Anton Villaruel, and Pam Yan-Santos.