Taking a Leap of Faith

A deep dive into Mark Justiniani’s Void of Spectacles.

Words and Photos Amanda Juico Dela Cruz

April 13, 2024

In Masha Gessen’s award-winning yet highly-controversial essay In the Shadow of the Holocaust, they pondered on the role of glass in memory culture, com- mending at first the efforts of Berlin in looking at its own crimes through memo- rials and museums, but later condemning how these efforts “began to feel static, glassed in, as though it were an effort not only to remember history but also to insure that only this particular history is remembered—and only in this way.”

But history is not supposed to be just remembered as an inanimate artifact of the past, trapped in its display case in an angle favored by its curator, passively sitting on its pedestal as visitors walk by. History is studied supposedly to provoke questions: Why did it happen? No, really, why did it happen? It is not supposed to be static and glassed in—a spectacle worthy of a few minutes of attention. Instead, learning history should urge actions, if not further questions. A docent asked me (but the question felt to me more like a provocation) after getting off the platform of the Capital, the second module in the Arkipelago, “Are we ready for change?”

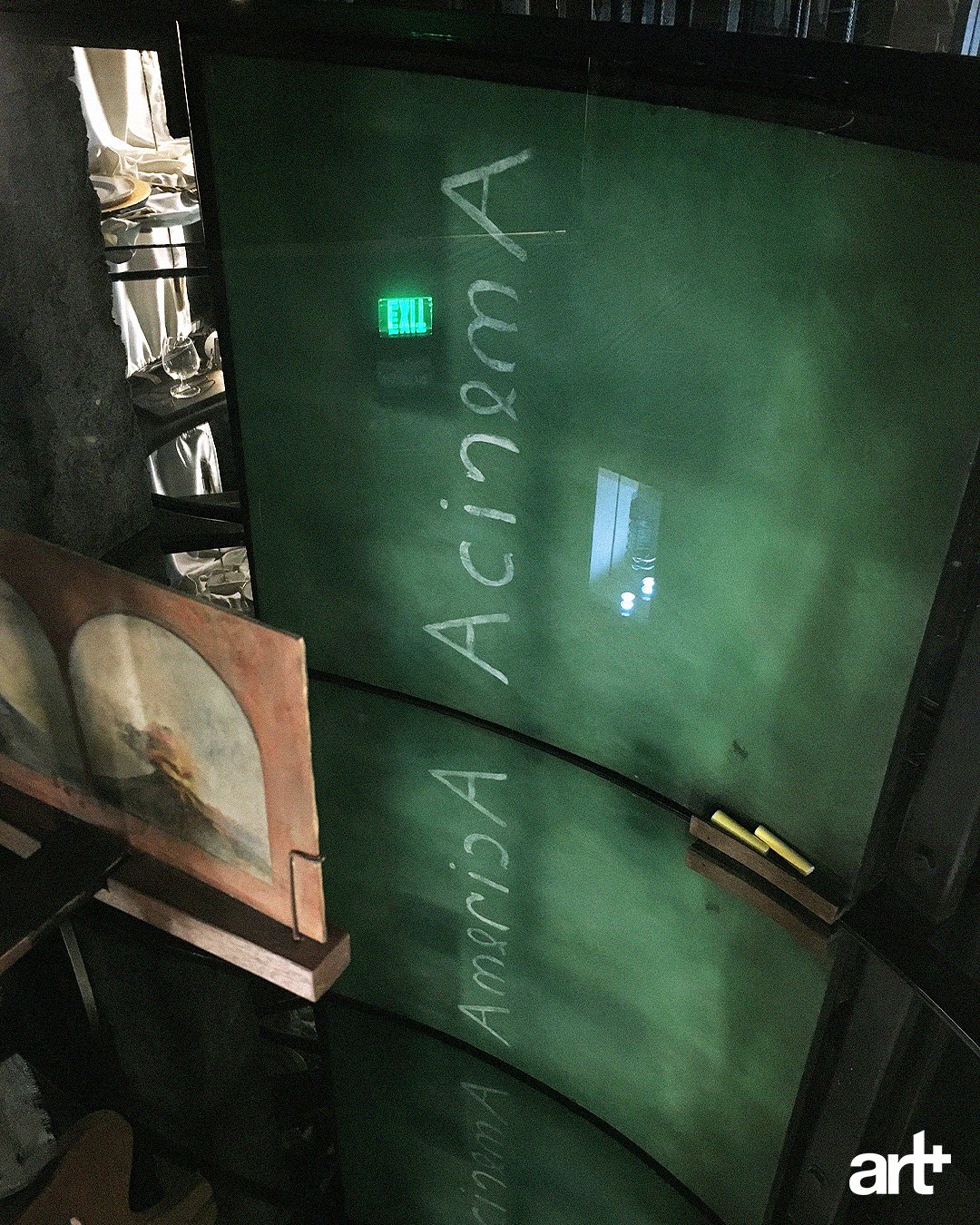

Mark Justiniani’s Infinity series of installations did not shy away from the use of glass, but unlike those condemned by Gessen, Justiniani’s works did not trap the artifacts-slash-art objects into the void of remembrance. His installations – particularly his Firewalk by the entrance of the gallery, Arkipelago that occupies much of the space, and then Well that concludes the Void of Spectacles: Reflections on Passages Through Time and History at the Ateneo Art Gallery – urged us to step into the very void of history. Talk about taking a leap of faith, not in the Kierkegaardian sense of believing in something that can never be proven, but in the sense that takes the risk of falling into the vast darkness with the hope that it will do us good. After all, what was in that void?

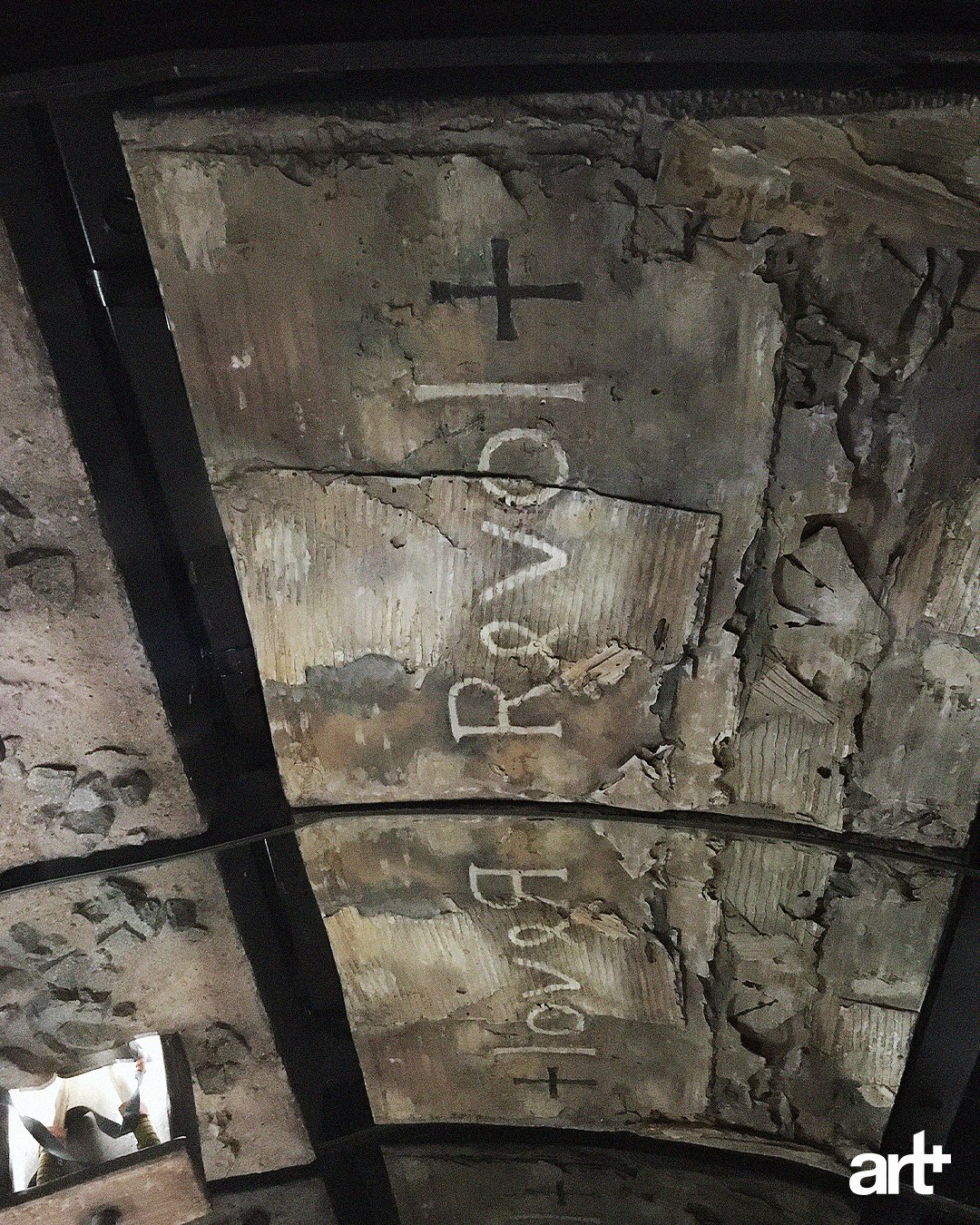

There must be something in the very nothingness underneath my feet. True. In the first module of Arkipelago titled Province, referring to the artist’s province of Negros Occidental, agriculture in the form of sugarcane harvesting anchored the rest of the panels. One panel contained a manual calculator and a farmer’s ledger of their debts to their landowners. In another panel were keys of a piano, the musical instrument of the affluent and the influential, emerging from beneath the ground, arranged as if a serpent slithering, preparing to attack when one least expects it. And then there was one with a curtain reminiscent of a confessional, with its balcony hacked by a cane knife. There should be hundreds of narratives that can be created out of these panels, the docent told me. What I remembered was a series of news reports upon seeing these elements in the installation, which led me to ask: Why did the killings in the region have to happen?