Dance of Ink

A retrospective on modern ink master Liu Kuo-sung sheds light on his trailblazing experimentation.

Words Jewel Chuaunsu

February 20, 2024

Liu Kuo-sung. Dance of the Black Ink. 1963. Ink on paper, 47 x 85 cm. Gift of The Liu Kuo-sung Foundation. Collection of National Gallery Singapore.

Throughout his career, artist Liu Kuo-sung has been instrumental in redefining the boundaries of ink painting and merging traditional Chinese and Western art philosophies. He continues to inspire artists worldwide with his innovative approach to the medium.

Liu Kuo-sung: Experimentation as Method at the National Gallery Singapore is a retrospective spanning seven decades of Liu’s artistic career, with over 60 breathtaking ink works and archival materials from his personal collection. The curatorial team behind the exhibition developed the curatorial narrative around the artist’s experimentation, from the early phase of his modern ink painting style, to developing techniques beyond the brush, and his various series including the Space, Jiuzhaigou, and Tibet series.

Liu Kuo-sung at Liu Kuo-sung_ Experimentation as Method, National Gallery Singapore. Photo courtesy of Joseph Nair, Memphis West Pictures

Exhibition view of Which is Earth section in Liu Kuo-sung - Experimentation as Method

Exhibition view of Which is Earth section in Liu Kuo-sung - Experimentation as Method

Born in 1932 in China’s Anhui province, Liu settled in Taiwan in 1949, where he later graduated from the Fine Arts Department of the National Taiwan Normal University. In his art education, he studied ink painting and was also exposed to Western painting.

Liu became a founding member of the Fifth Moon Group, which made important contributions to Taiwan’s modern art movement from the 1950s to 1970s. Liu’s early style took inspiration from Western modern masters such as Henri Matisse and Pablo Picasso, as well as American expressionism. He delved into creating abstract paintings along with the rest of the group.

As he was reflecting on modernity, Liu remained preoccupied with a key artistic concern: How does one contribute to the development of modern Chinese art? Dissatisfied with the imitative method of learning Chinese painting, he reasoned that painting based on Western modern art was also a form of imitation. Thus, the spirit of Chinese modern painting relied on the creativity of the artist.

In 1961, Taiwan’s Central Museum and Taipei Palace Museum organized the traveling exhibition Chinese Art Treasures, which featured works by some of the most prominent artists in Chinese art history for the first time. Liu was able to see a preview of the exhibition at Taiwan Provincial Museum. He was struck by the Northern Song monumental landscapes, particularly Fan Kuan’s “Travellers Among Mountains and Streams” (c. 1000).

Though he had favored abstraction over realism, Liu’s encounter with Fan Kuan’s masterpiece was revelatory. In an interview with Rudy Tseng, he recalled: “Although ‘Travellers Among Mountains and Streams’ is a work of realism, none of its poignant beauty, its luminous magnificence, was at all compromised. In other words, it doesn’t matter which painting style an artist employs, it only matters how the artist captures the expressive potential of art with the chosen style.”

Liu’s fundamental views on painting shifted when he realized that the most important thing is for the artist to express his ideas coherently and powerfully. He returned to the medium of Chinese ink, looking for inspiration for modern painting within the Chinese tradition.

Liu experimented with different painting materials and various papers, and later developed the “Kuo-sung Paper”—thick cotton paper with various fibers on its surface. Using this paper, Liu came up with a technique he called “texturing by plucking and flaying” wherein he would carefully tear the fibers on the paper surface to create textural white lines. Liu’s bold ink strokes flowed and interacted with the white lines.

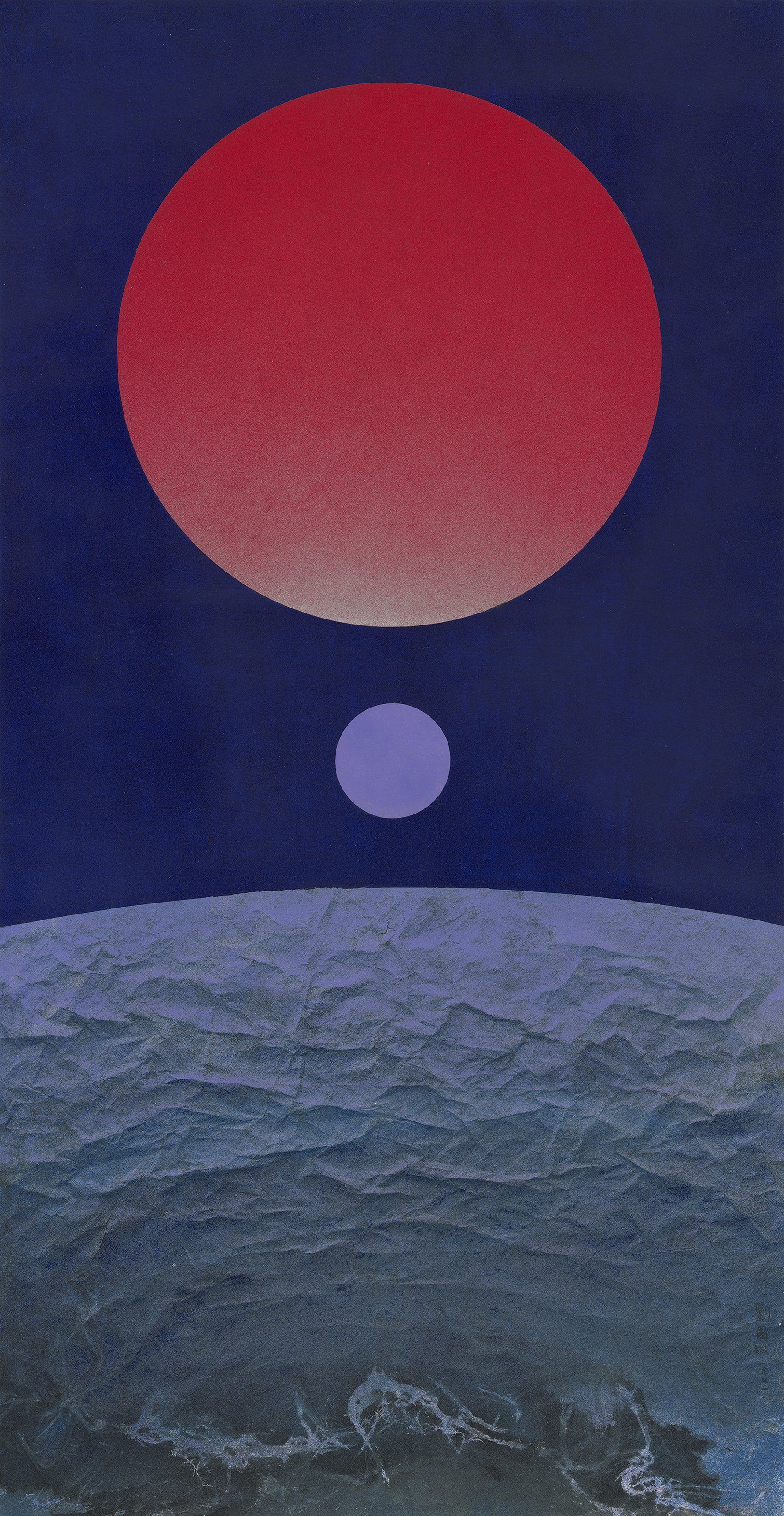

From the late 1960s to the early 1970s, Liu created his Space series of paintings inspired by photographs taken on the Apollo 9 mission in 1968, especially “Earthrise”—a photo taken by astronaut William Anders of the illuminated Earth appearing over the lunar horizon. Liu expressed that he was “moved by the beauty of nature and space and the intelligence of mankind” after seeing the photograph.

Liu’s Space series was characterized by circle shapes, which may represent the Earth, moon, or sun. In this series, the natural imagery of Chinese landscape painting extended to the cosmic landscape of the universe. Liu would revisit the series from 2000 onwards.

Liu Kuo-sung. Moon Walk. 1969. Ink and acrylic with collage on paper. 59 x 85 cm. Private collection.

Included in this series is Liu’s collage work “Moon Walk” (1969), which incorporated a photograph from LIFE Magazine that captured astronaut Buzz Aldrin walking on the moon during the Apollo 11 mission.

Liu continued to explore possibilities in ink painting and boldly proposed to “overturn the centre tip, overturn the brush” to allow artists to break free from traditional calligraphic brushwork. He developed brushless techniques such as water rubbing and the steeped-ink technique.

In water rubbing, Liu would fill a bathtub or basin with water and drop ink on the surface, letting the currents create ripples and marbling. He would delicately place a sheet of paper on the water’s surface to take the ink.

In the interview with Rudy Tseng, he explained: “After extensive experimentation with my water rubbing technique, I had more or less decided on the kind of effects I would like to render. However, the ultimate appearance of the resulting shapes or lines cannot be completely controlled. I can only manipulate the forms for the most part – maybe for about 70 to 80 percent of the time – the remaining 20 to 30 percent can only be left up to chance.”

For the steeped-ink technique, he would put two sheets of paper together and paint on one sheet, allowing the ink to seep through onto the desired surface. The air pockets between the papers also affect the ink and create lines and shapes.

From the 1980s onwards, Liu traveled extensively through China and was inspired by nature. From 2000, he started working on two of his most well-known series of paintings, which were inspired by the lakes of Jiuzhaigou and the snow-capped mountains of Tibet. His panoramic compositions of undulating mountains hark back to the magnificence of the Chinese landscape paintings from the Northern Song Dynasty.

Liu dedicated much of his energy to teaching, with the aim of nurturing a new generation of modern ink painters. He became the Chairman of the Department of Fine Arts at the Chinese University of Hong Kong where he established the modern ink painting curriculum. And as he exhibited in major cities across Mainland China, he gave lectures and demonstrations wherever he went. Driven by a mission to champion the modernization of Chinese painting, he encouraged his students to freely express themselves and to experiment with techniques and materials: “Seek first to be unique, and then to be excellent.”

Liu Kuo-sung: Experimentation as Method runs until 25 February 2024. The exhibition is shown at National Gallery Singapore, Level 4 Gallery and Wu Guanzhong Gallery.