Beyond the Red

As Doktor Karayom, artist Russel Trinidad’s vermillion works are marked by gore, folklore, and street smart humor. He talks about how mischief and getting curious about fear shapes his art.

Words Khyne Palumar

Photo courtesy of Doktor Karayom

September 26, 2025

Profile Photo of Doktor Karayom

Russel Trinidad began calling himself Karayom over a decade ago, when he was a street artist coming up from Pasay City. The name became both a tool (“kailangan ng karayom para mag inject ng gamot o lason,” he says) and a mantra of sorts to keep pushing, even if making it in art meant figuratively passing through the eye of a needle (“pumasok sa butas ng karayom.”)

A Fine Arts graduate from the Technological University of the Philippines, Trinidad later added “Doktor” to his moniker partly in jest, and partly as social commentary. “Sa prankang pananalita, mababa tingin sa artists dito. Ang typikal na pinagmamalaki ng magulang, doctor, engineer, o lawyer. Kaya nilagyan ko ng ‘Doktor’ para tunog matalino,” he says. (Frankly speaking, artists aren’t held in high regard here. Parents typically brag about having a doctor, engineer, or lawyer for a kid. So I threw in ‘Doktor’ to sound smart.)

But anyone who’s paid close attention to Doktor Karayom’s art knows that behind his proclivity for gore and grisly dismembered figures is Trinidad’s sharp commentary and deliberate satire.

Isla Inip (2018)

One example is his 2018 showcase Isla Inip (an anagram of Pilipinas). Trindad created it as a recipient and part of the Cultural Center of the Philippines’ Thirteen Artists Awards. Shown at both the CCP and the Palais de Tokyo in Paris, Doktor Karayom’s installation resembled a bloodied crime scene: walls and ceiling painted in his signature red, with smaller sculptures swarming a 13-foot Jose Rizal cadaver. The piece raised a few eyebrows, as instead of offering a sentimental take on nationalism, Trinidad posed a moral question.

“Madaming nagtatanong bakit may bangkay ng pambansang bayani natin—kasi matagal na siyang patay at nabubulok. Pero bilang mga nakatira sa bansa na ito, may ginagawa ba tayo para hindi bumaho yung tinitirhan natin?” he muses. (Many have asked why our national hero’s corpse is there—it’s because he’s long dead and rotting. But as people living in this country, what are we doing to stop our homeland from stinking?)

Trinidad, now based in Cabuyao, Laguna, spoke with Art+ after returning from a residency in Liverpool, in the UK—his third of four residency grants from the 2023 Ateneo Art Awards, after earlier stops in Toronto, Canada and Bendigo, Australia. The final leg will be in Lucban, Quezon, his family’s hometown, where he’s eager to stage a “homecoming show.”

Doktor Karayom’s Liverpool works

As in past residencies, Trinidad mounted a show during his two-week stay at Liverpool, even though he was encouraged to simply soak in the creative scene. “Sayang kase,” he says, adding he could kill time playing tourist but would much rather “tell a story.” One standout piece is Napupuno Ka Ng Grasya, an 8x6-foot sculpture made from repurposed “drop sheets” or plastic used to catch paint drips off the floor. Trinidad seamed the sheets using a dorm iron and inflated it with a fan. “Sigaw ako ng sigaw nung nag-work, akala ko mapapagalitan ako,” (I kept howling when it worked—I thought I’d get in trouble), he recalls with a laugh.

Trinidad thrives on instinct and curiosity, guided more by feeling than rigid planning. “Hindi ko masyadong pinaplano—pinapakiramdam ko lang kung saan ako dadalhin. Laging may hindi pantay, sablay, hindi perpekto. Inaayos ko, pero hindi pa rin sakto. Didikit ba ’to? Tatayo ba ito? Lolobo ba ito? Doon ako na-e-excite,” he says. (I don’t plan much—I follow where it takes me. It’s always uneven, off, imperfect. I try to fix it, but it never turns out perfect. Will it stick? Will it stand? Will it inflate? That’s what excites me.)

He adds, “May mga ideya akong baon, pero ang lagi kong hinahanap ay ‘yung makakagulat. Suwerte rin na palagi akong nasusurpresa sa sarili kong gawa.” (I start with a few ideas, but I always look for something that will surprise. Luckily, I often end up surprising myself with my own work.)

From KITASABITAK

That experimental energy has taken him across a wide range of media over his 13-year career: from graffiti and red ballpen drawings to embroidery, animation, murals, fashion (via collabs with Lakat Sustainables and Linya-Linya), and sculpture. His first solo exhibit Santong Pikon in 2015 featured paper mache, resin, and fiberglass works made inside a cramped apartment—“Siguro tatlong hakbang lang siya”—where he slept beside a life-sized Jesus sculpture and inhaled fumes day in and day out. “Hindi siya healthy,” he admits.

His signature red pen drawings came full circle with Grade 3, a humorous and gory visual diary released last year. It draws from his childhood and visits to Quezon to see his grandfather—a fisherman and mananambal (folk healer) who inspired Trinidad’s love for folklore, mysticism, and horror. He recalls frequently getting sick as a child on suspicions of disturbing a dwende patch.

From KITASABITAK

“Kumakatas sa gawa ko yung mga kwento ng folklore at katatakutan. Mahilig kasi ako sa misteryo. Kahit na napapaliwanag ng siyensiya ang mga bagay at naiintindihan ko—ayokong mawala yung misteryo. Pakiramdam ko kailangan pa rin natin ng hiwaga. Kailangan ng mundo ng misteryo para umikot,” he says. (Those stories just seep into my work—folklore, ghost tales. I’ve always been drawn to mystery. Even if science explains things, and I understand it, I still don’t want the mystery to disappear. I feel like the world needs mystery to keep turning.)

Beyond the gore, Doktor Karayom’s work digs into the root of horror: fear. “Para sa akin, ang horror ay pangkabuuan na nararamdaman ng tao sa kaibuturan,” he says. (To me, horror reflects something deeply human.) “Tayong mga Pilipino, palaging may takot. Takot mawalan, takot sumobra, takot na mapagsamantalahan. ‘Yun ang gusto kong tuklasin: bakit tayo laging takot?” (As Filipinos, we’re often afraid—of losing, of excess, of being taken advantage of. That’s what I want to uncover: why are we always scared?)

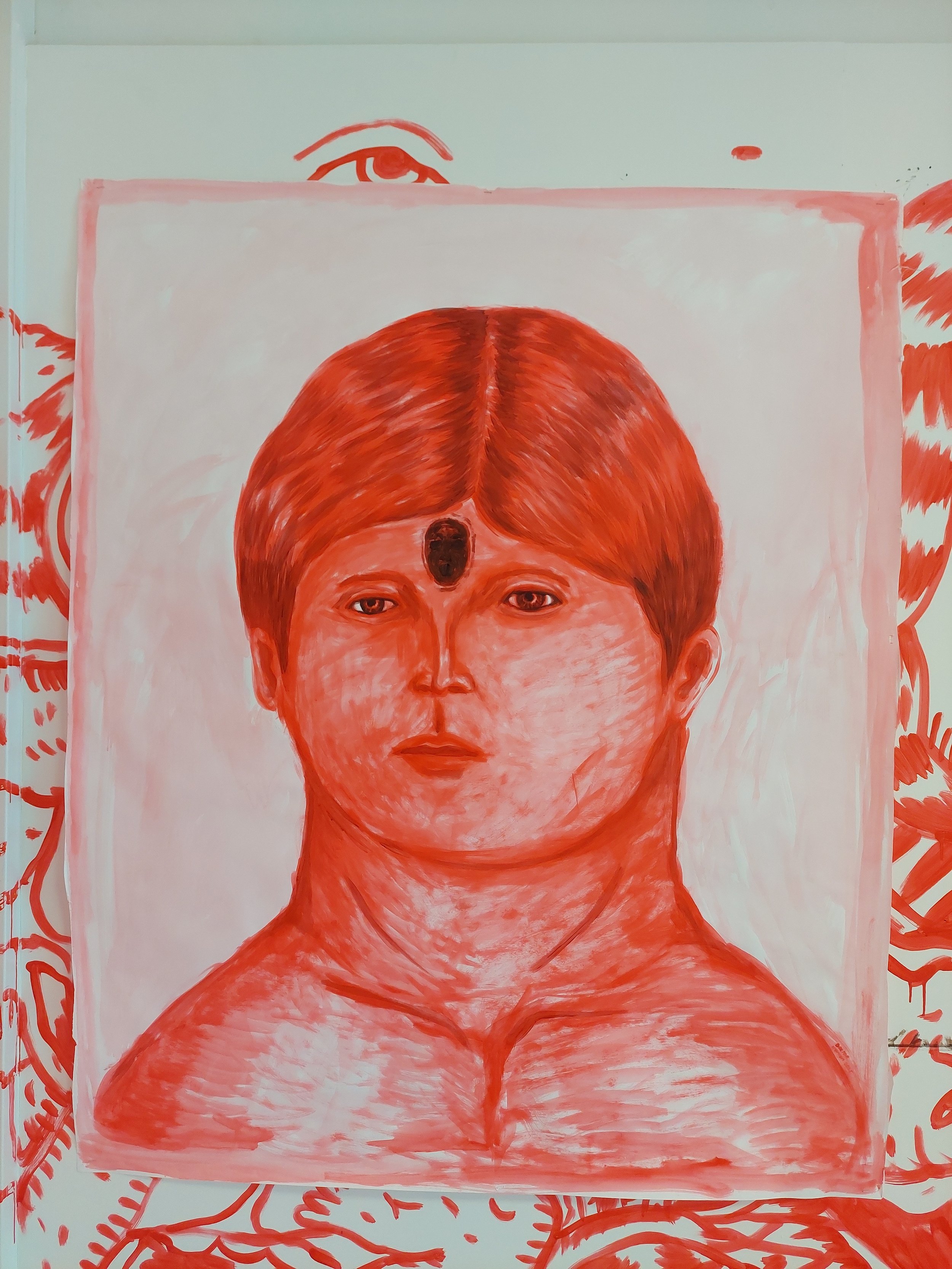

TAOSANOO

“Sabi nila, nakakatakot daw ’yung mga piyesa ko. Pero sa totoo lang, may aral siyang dala,” he continues. “Ang kaso, ang tingin ng tao: ‘Ano ‘yan? Labas laman? Labas utak?’ Siguro gano’n talaga ang reaksyon pag may nakita silang nakakatakot—hindi na nila ini-explore. Kaya gusto kong sabihin: ‘Wag kayong matakot. Tuklasin niyo ‘yung takot. Parte ‘yan ng buhay natin.” (They say my work looks scary. But honestly, it carries lessons. The problem is, people see guts or brains and stop there. That’s how we react to fear—we don’t explore it. What I want to say is: don’t be afraid. Explore fear. It’s part of life.)

“Minsan maganda rin ang takot, kasi kinakalabit niya ‘yung utak mo. Pinapa-apoy ka niya, pinapaisip ka,” he adds. “Kaya gusto ko siyang laging nilalaro sa gawa ko.”(Sometimes fear is a good thing—it jolts your brain, lights a fire in you, makes you think. That’s why I keep returning to it in my work.)