Across the Sea

Filipina-American artist Nicolei Buendia Gupit weaves together migration, climate crisis, and diasporic identity in her latest exhibition, Tawid Dagat.

Words Jewel Chuaunsu

Photos courtesy of Nicolei Buendia Gupit and Kaohsiung Museum of Fine Arts

December 29, 2025

U.S.-born Filipina multidisciplinary artist Nicolei Buendia Gupit was raised in Los Angeles, California, where she migrated with her parents. In a city with a large Filipino community, Filipino culture shaped their daily lives through food, language, and cultural practices. But, as Nicolei reflects, “there was still a lingering sense of not fully belonging, a feeling that sometimes surfaces in my work.”

Her time working in Asia—teaching English in South Korea and Taiwan—heightened her awareness of her cultural identity as a Filipino-American, navigating the duality of being both an insider and outsider. This experience prompted her to reflect more deeply on her family history and her positionality within broader historical, social, and political contexts:

“It led me to explore the colonial histories of the Philippines during my studies, to more deeply unravel the legacies that shape migration, and the contemporary issues that affect Filipinos at home and abroad.”

In the 1970s, Nicolei’s mother and relatives left the Philippines to escape poverty and political instability during the Marcos Sr. era. They felt compelled to leave in order to support their children and aging parents, though they ultimately returned to the Philippines later in life.

“Their stories echo the stories of others: at its core, migration is survival, a search for stability when home no longer feels secure. I think of my mother and her siblings crossing the Pacific Ocean for us, and I see migration as being characterized by fragility, necessity, and resilience.”

Nicolei earned a BA in Studio Art from Williams College in 2013 on a full scholarship, later pursuing an MFA from Michigan State University. After completing her MFA in 2022, she was awarded a Fulbright grant to the Philippines to produce and exhibit art focused on the human toll of climate change. Based primarily in Los Baños, Laguna, she led eco-poetry and watercolor workshops, volunteered with Global Shapers Manila, participated in a funded art residency in Cavite, received the Art Fair Philippines Residency Award, and publicly exhibited her work at Art Fair PH. Her art career gained momentum in 2022, allowing her to actively exhibit in the Philippines.

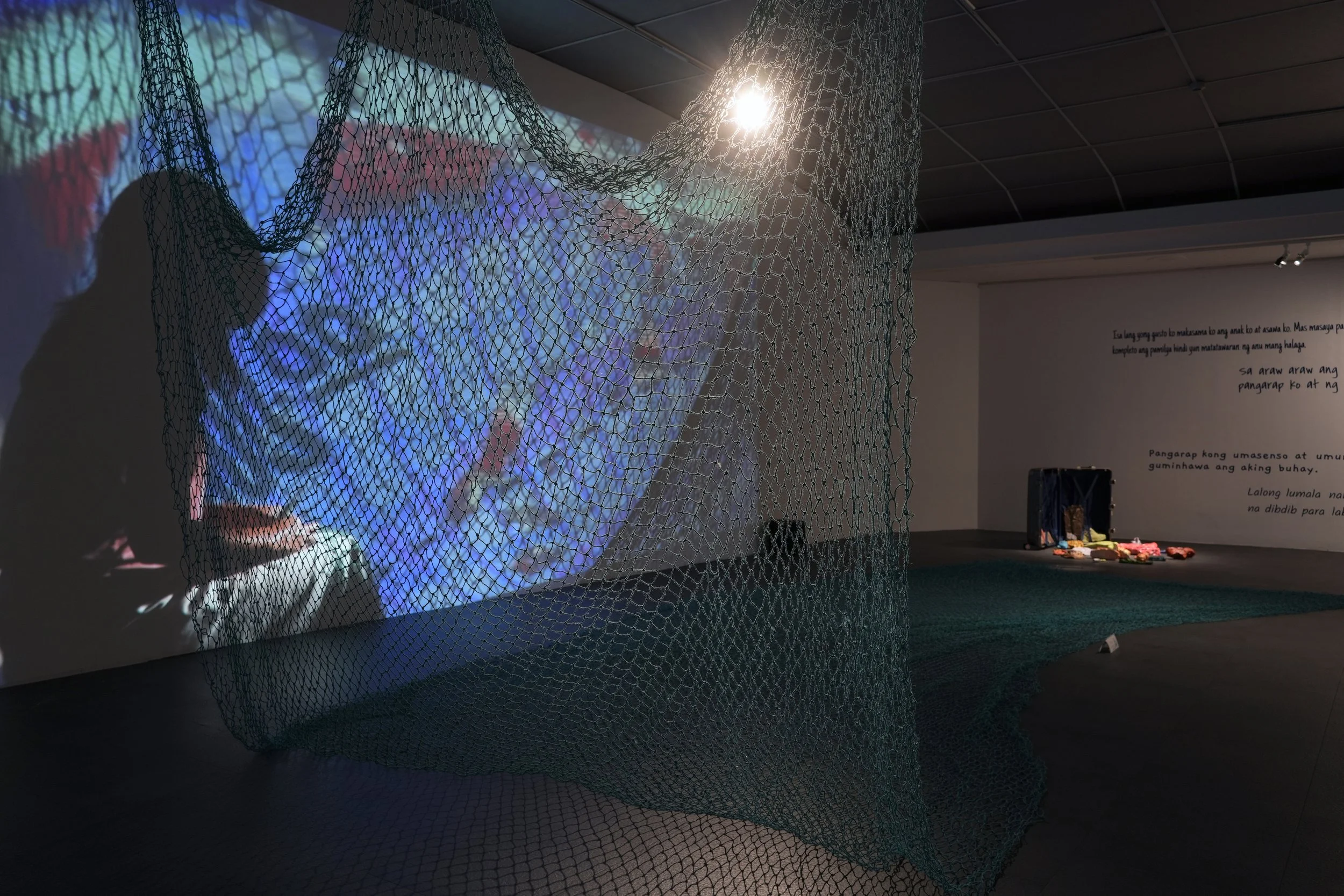

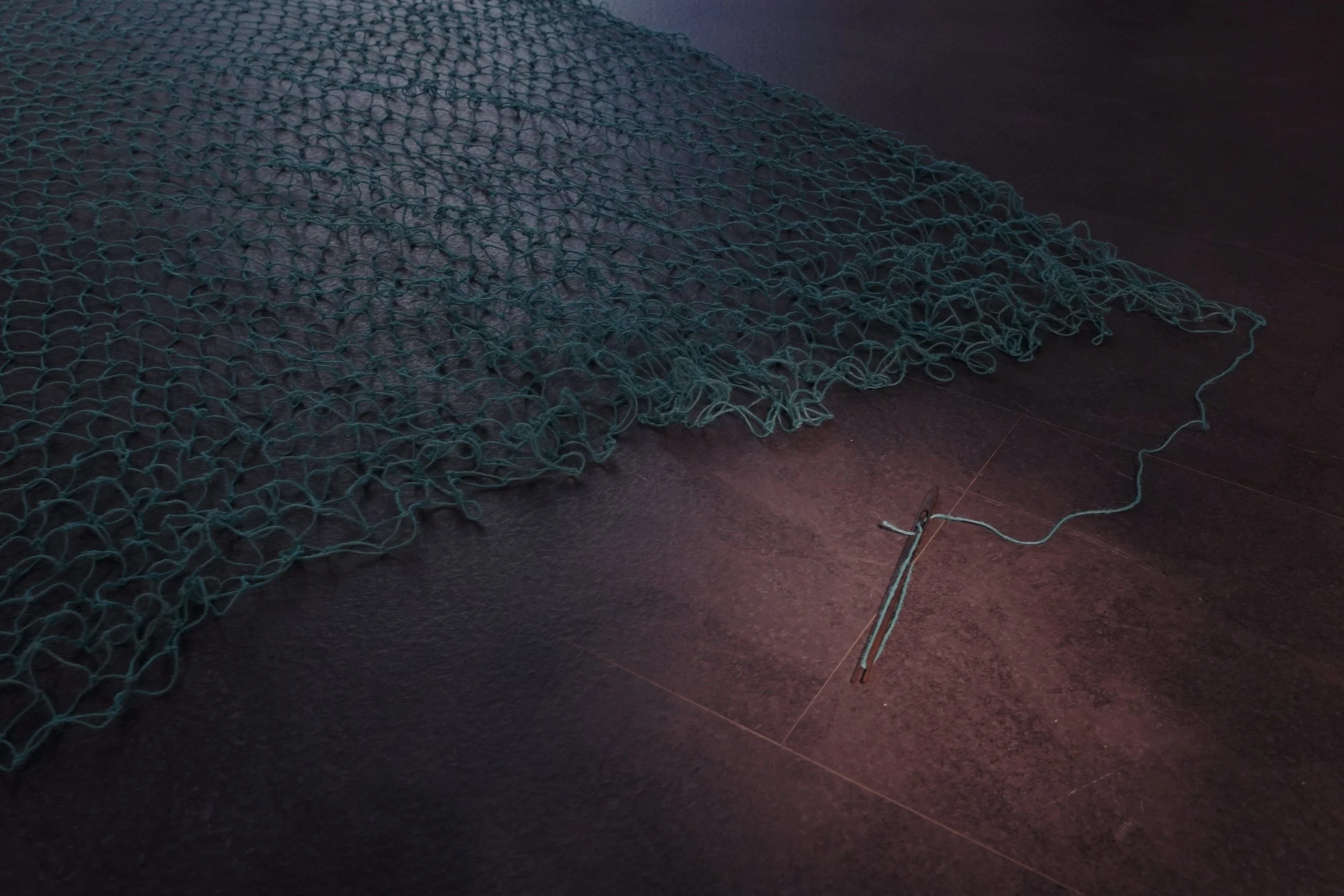

Even after returning to the U.S., Nicolei continued to engage with the Filipino community. In July 2024, she was a resident artist with Emerging Islands in San Juan, La Union, where she led an eco-art-making and storytelling workshop with a local fishing community. This experience led to her 2025 video work I Unravel the Seas, now being presented at the Kaohsiung Museum of Fine Arts in Taiwan.

Invitations for solo exhibitions continue to bring her back to the Philippines, including last year’s Mother/land at Altro Mondo Creative Space and upcoming shows in Metro Manila slated for 2026 and 2027.

“These opportunities allow me to remain in contact with the communities that provide a vital refuge in my life and my artistic practice,” Nicolei says.

Nicolei uses familiar objects and references to invite diverse audiences to “step into the specific histories of the Filipino diaspora.” In her Pamilya series (2022), she chose the dining table as a central motif—“a place of gathering, of eating together, of absence and presence.”

In In the Age of Abundant Scarcity (2023), presented at Art Fair Philippines, she created an installation of 44 resin sculptures shaped like plastic water bottles, each filled with waste materials collected from local lakes and rivers. The work addressed the inequality of access to clean water.

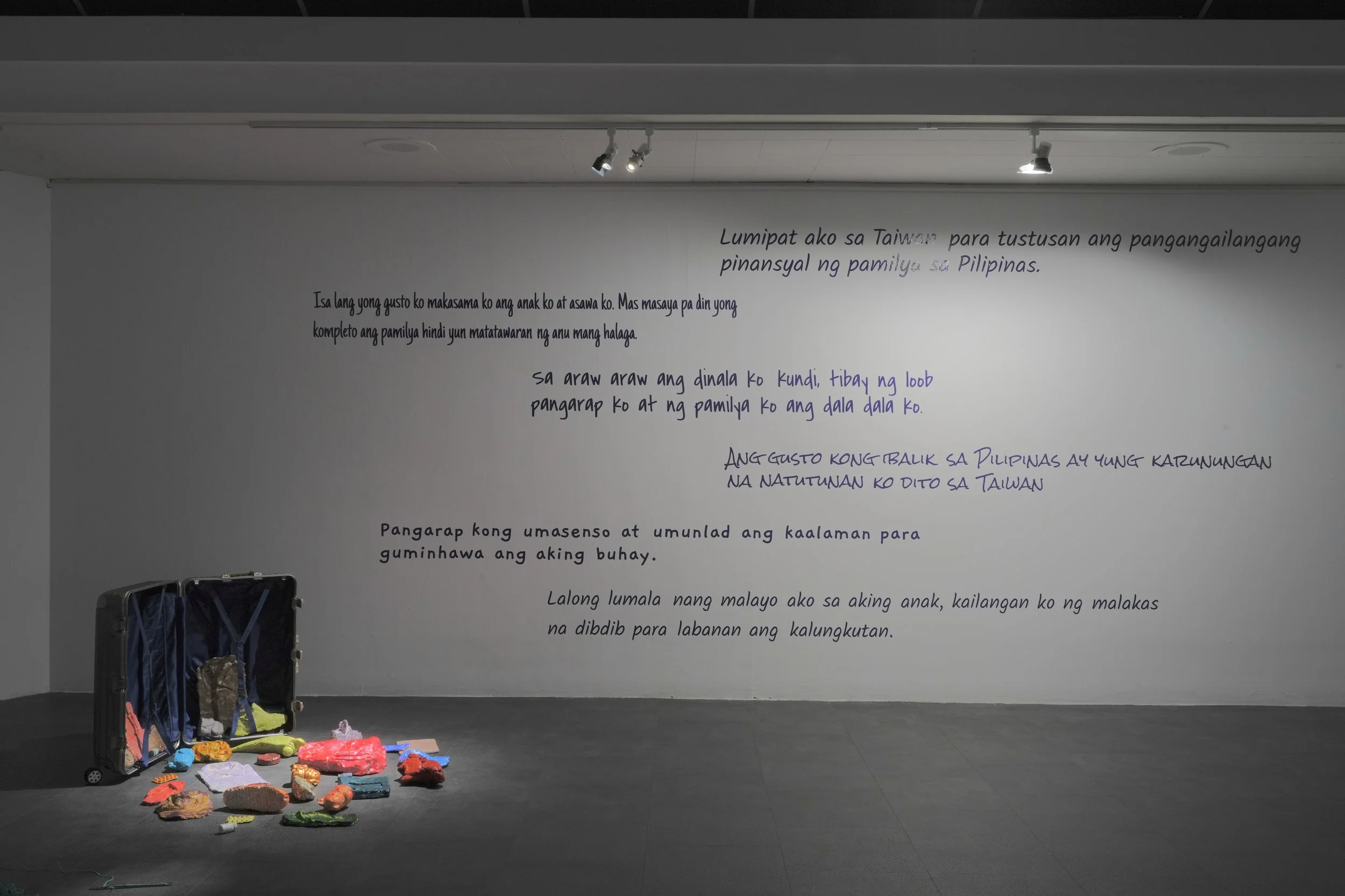

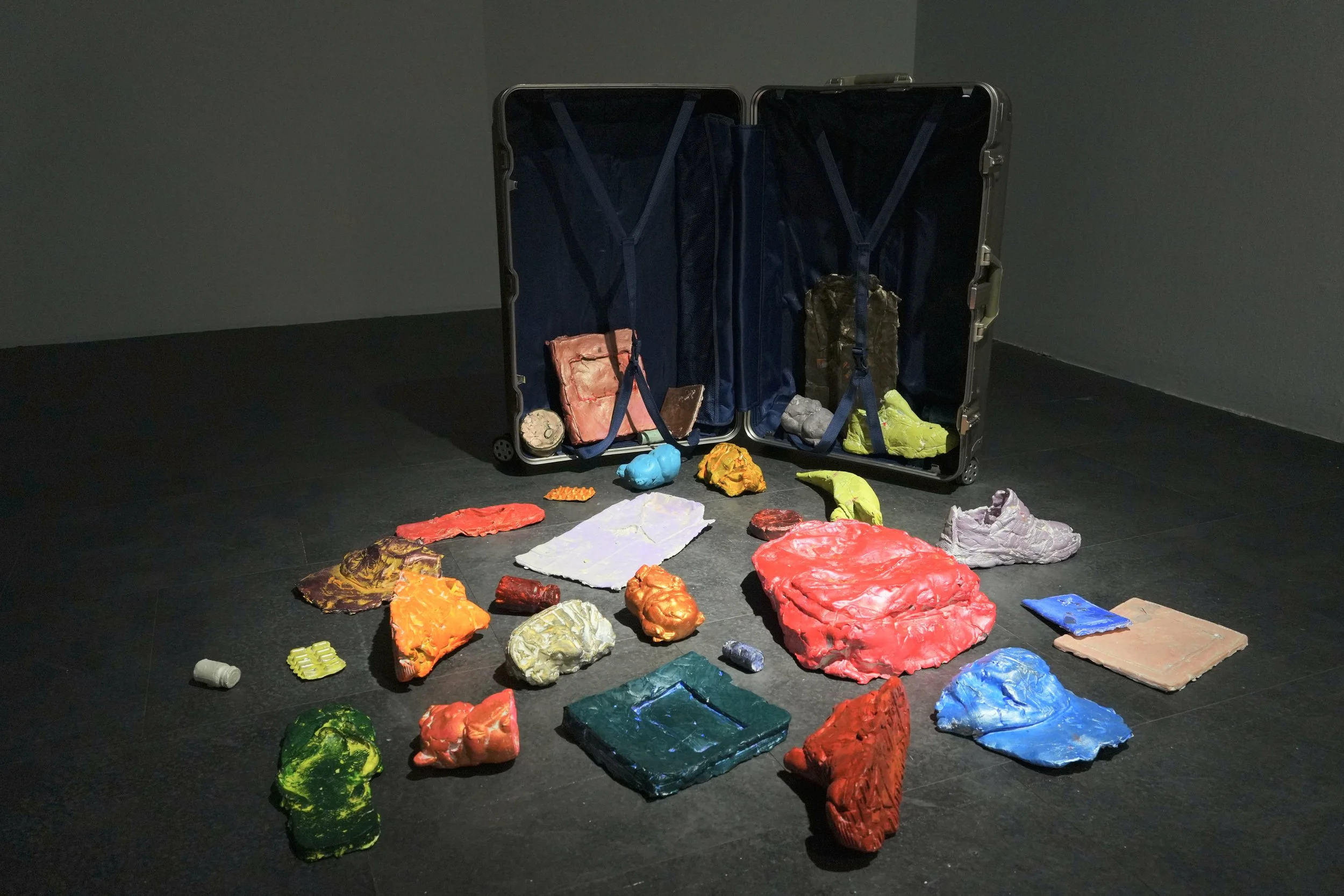

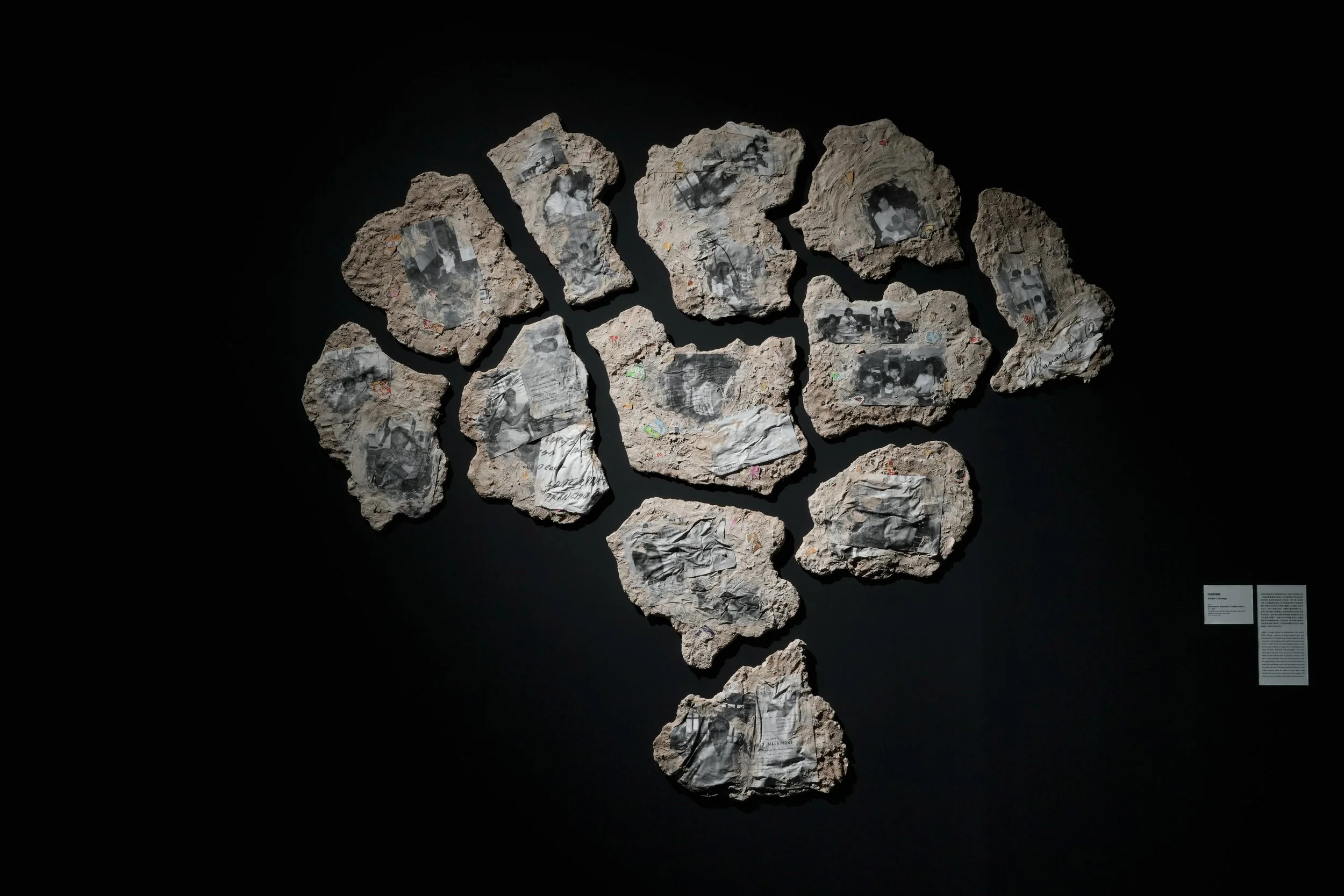

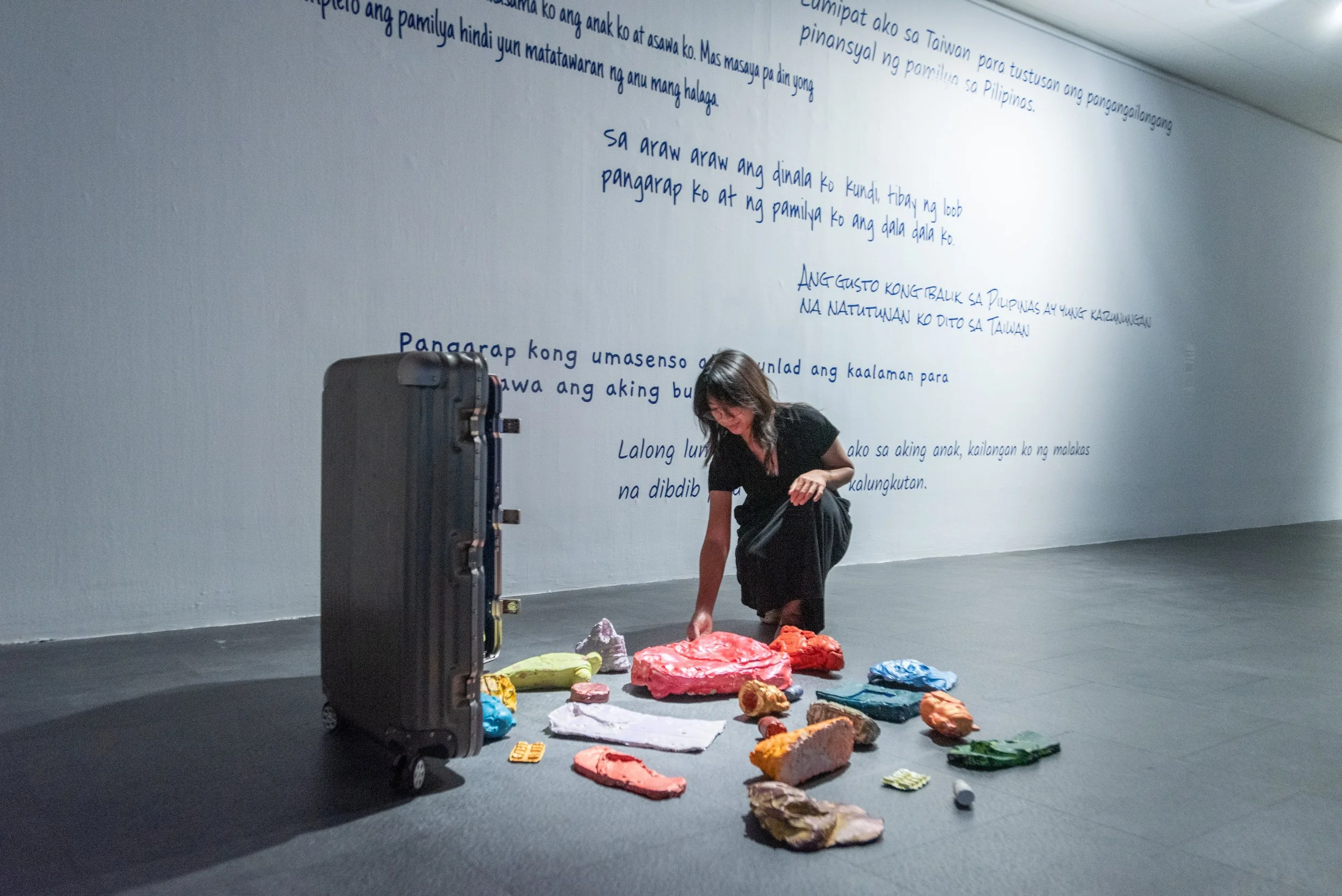

Her practice combines traditional and unconventional materials—from plant fibers and paper pulp to lottery tickets and video. In her mixed media installation swerte, she cast objects brought by Filipino migrants to new countries, incorporating lottery scratcher tickets.

“As part of the project, I interviewed members of the Filipino migrant communities to better understand the connections between migration, luck, gambling, and ‘acts of faith,’” she explains.

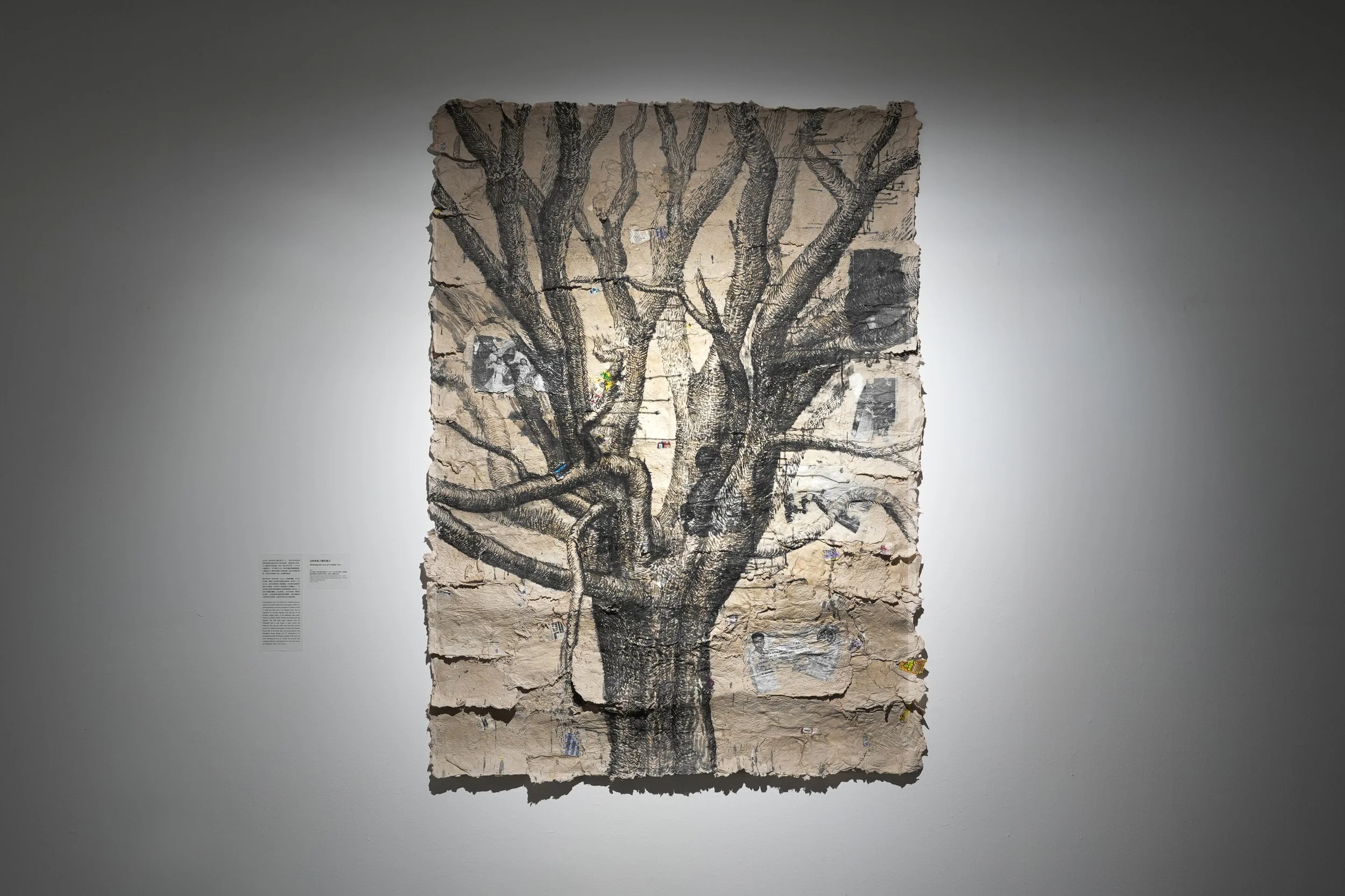

Nicolei also incorporates techniques like papermaking, net weaving, photocopying, and casting. Net weaving connects her to traditional crafts and to ancestors who fished in Manila Bay. Photocopying and casting allow her to explore themes of displacement and “how diaspora produces both copies and transformations of the motherland.” The versatility of papermaking—and how paper can be reshaped—mirrors the fluid, adaptable nature of the migrant experience.

Her work has been exhibited globally at art spaces including spazioSERRA in Milan, Italy; Altro Mondo Creative Space in Manila, Philippines; the Pier-2 Art Center in Kaohsiung, Taiwan; the San Jose Museum of Quilts & Textiles in San Jose, California; and the Painting Center and A.I.R. Gallery in New York City.

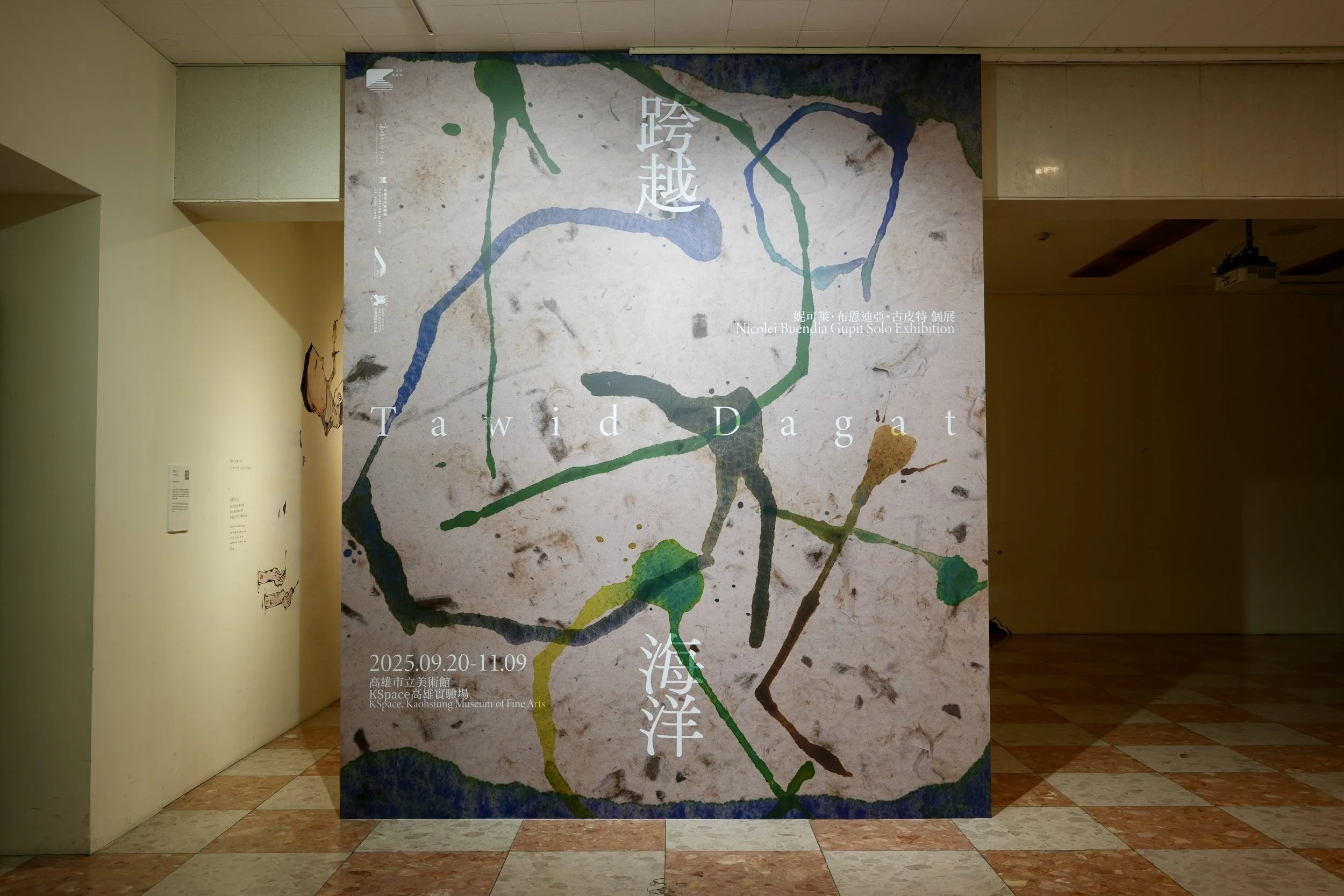

Nicolei’s latest solo exhibition, Tawid Dagat, features 15 works created since 2021. In an interview with Art+, she reflects on the exhibition’s themes.

“Tawid Dagat” translates to “to cross the sea.” What does this phrase mean to you personally, and how did it shape the vision for your exhibition?

For me, tawid dagat speaks to many kinds of voyages across uncertain waters: journeys to return to the homeland, to search for oneself, or to leave family to build anew. Tawid dagat is the act of leaving one shore and arriving on another.

I chose Tawid Dagat as the exhibition title because it weaves through many seemingly disparate themes in my work. In Tagalog, tawid dagat emphasizes the journey itself. Whether through my own return to Manila Bay, my mother’s migration to the United States and her later retirement in the Philippines, or the countless OFWs who cross seas to work in places like Taiwan, each work in the exhibition engages with water and journeying in some form.

The phrase carries layers of meaning that the English “to cross the sea” cannot fully capture. The “other side” may be across a river, a lake, or an ocean, and the crossing might happen by bangka, ferry, or even airplane. Without the hyphen, tawid dagat translates literally as “to cross sea”; with the hyphen, tawid-dagat can mean “overseas,” “abroad,” or “from across the sea.”

Conjugations of tawid express its multiple meanings: Magtatawid ng dagat kami bukas or Nagtawid-dagat siya para makahanap ng trabaho. Even the root tawid holds various meanings depending on context, as in tawid-gutom, “to tide over hunger,” where tawid becomes an act of bridging or survival.

Your exhibition explores Filipino migration narratives and the climate crisis. What drew you to explore these themes in conversation with each other?

My exhibition explores Filipino migration narratives alongside the climate crisis because my family is of the Filipino diaspora, and both migration histories and contemporary climate crises continue to profoundly impact our lives.

My work often begins with this personal grounding as a foundation because it is what I know intimately. Yet, I also expand beyond the personal, situating these stories within broader histories where migration and climate instability are both deeply individual and universally shared.

Climate instability and government corruption intensify the fragility of life in the homeland. Everyone in the Philippines knows: ecological disaster is a daily reality. It is no accident that the Philippines ranks first in the UN’s 2024 World Risk Report as the most vulnerable country to climate crises. When typhoons strengthen year after year, or when rising seas reach coastal homes, it becomes harder to imagine a secure future without leaving.

To examine migration and climate change together is to see how deeply intertwined the two really are. The climate crisis destabilizes lives, while migration emerges as both a response and a consequence. My work seeks to hold these realities together: the personal history of my family, the varied stories across the Filipino diaspora, and the global context of ecological crises. Together, they reveal broad narratives of survival, resilience, and the search for stability in increasingly uncertain times.

How do you see water functioning in your work as a symbol?

Water functions in my artwork as both a deep concern and an inspiration. I consider my family’s home in Rosario, Cavite, where accessing clean water can be challenging. We draw groundwater from a poso for daily needs, but for drinking, we must buy “mineral” water or refill our galon with filtered water.

Water, too, is what separates our home in the Philippines from my generation’s lives in the US. The Pacific Ocean is among the large bodies of water that divides the world into time zones. In this sense, water is not only a material resource but also a condition of life that is intimately political, ecological, and personal.

Typhoons bring torrential rains and deadly floods that can submerge entire communities, yet safe drinking water remains a commodity tied to class, geography, and power. Efforts at flood control often reproduce inequality, mired in inefficiency and corruption at all levels. These contradictions, between scarcity and overabundance, shapes the lives of Filipinos in the Philippines, and perhaps many parts of the Global South.

In other words, water is never neutral; it is entangled with sociopolitics, class, and governance.

At the same time, water carries deep resonance. It is fundamental to survival and humanity. The human body is made mostly of water; what flows through rivers and seas also flows through us. In the Philippines, water defines geography and daily life. Water separates every island, but water also makes travel and connection possible. Beyond the archipelago, oceans divide nations even as they bridge them.

Water is both boundary and passage, destruction and sustenance. It is necessary to sustain life, yet sold as a commodity. In my artwork, I return to water precisely because of these contradictions. For me, water is not simply a subject but a condition of human existence: one that shapes my family’s migration story and the lived realities of the Philippines.

If you could speak directly to young diasporic Filipino artists today, what advice or encouragement would you offer?

Take risks, experiment boldly, and commit to your passion. The path of art is rarely secure, and practical pressures are strong, but passion gives your work purpose. Commitment requires embracing uncertainty and inviting the possibility of discovering new things. To experiment boldly is to try new techniques, mediums, or materials without fear of failure or criticism.

For diasporic artists, living between cultures and geographies can create a sense of not fully belonging—but this in-between space is also a source of insight and perspective. To follow your passion is to embrace that complexity and channel it into your art.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Tawid Dagat is on view from September 20 to November 9, 2025 at the Kaohsiung Museum of Fine Arts. The exhibition is co-organized by the Kaohsiung Museum of Fine Arts and Pier-2 Art Center Artist-in-Residence Program, in collaboration with the Manila Economic and Cultural Office (MECO) in Taiwan,